Each Chobi Mela offers another reason to further explore the realms of photography and to define new heights for the festival itself. When a tag like ‘Asia’s largest international festival of photography’ or ‘the world’s most demographically inclusive festival’ bestows itself upon Chobi Mela, it only heightens the world’s expectations of us. To live up to these expectations, we reach out to people who can help us make the festival better. And Salauddin Ahmed, notable Bangladeshi architect, is one such person acting as a guest curator for Chobi Mela VIII.

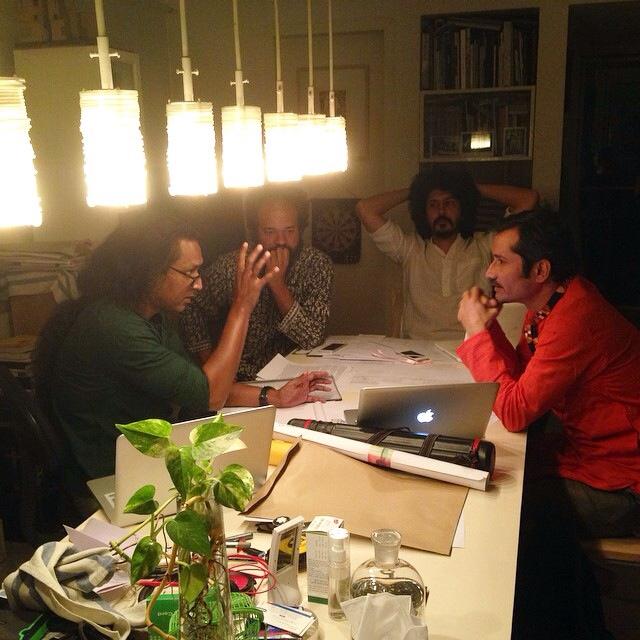

Here, Munem Wasif, another curator of Chobi Mela VIII and a notable photographer himself, strikes up a conversation with Salauddin Ahmed to help us understand better how architecture can possibly be merged with photography.

Munem Wasif: Salauddin bhai, you are working as a guest curator in Chobi Mela but you come from a completely different kind of background, which is architecture. I think photography and architecture have a very interesting relationship because both deal with space and light. As you are working with some particular artists here at the Chobi Mela VIII, can you just talk in general about your experience so far? How are you looking at certain kinds of photographers?

Salauddin Ahmed: Well, the more I think about the discipline that I am in and the other disciplines that are around architecture, I no longer see any sort of boundary for each. I think of them as one. I, as an architect, express an idea through a built space; photographers find themselves constructing their images to convey their ideas. They are all creative journeys that end in one thing- bringing out certain hidden layers of society through their perceptions, through a meditative gaze. So, working as a guest curator, for which I don’t know if I’m the right person or not, I often think as a photographer or a painter or any other creative individual – I think of the ways we use just to look at an image to give a sort of boundary to that image within the frame.

But the frame is just an excuse to express much larger aspects of that image. So as an architect, I thought Chobi Mela was a wonderful opportunity to work with photography and with photographers. Whatever I think lacks in the conventional medium of viewing photographs is an opportunity for me, as an architect, to work around it. I want to work on stretching out the canvas and I want to bring it out to a level where the audience can actually not just look at an image from a distance, but rather be involved with the image. So I took the challenge of bringing out the energy that I sense in each image given to me to work with.

It is not only how the image is being reviewed but also how someone else is also looking at the image that is part of that experience. Hopefully, it will bring new dimensions. I’m not the first one to think along this line, but I think, personally, I was really struggling to find out how I can extract the inner strength of an image through an architectural space, so that the experience could be viewed by a third eye, where this ‘third eye’ is the audience in that space.

MW: Let’s be a little bit more specific now. You are curating the first gallery at the Shilpokola Academy. There, we are showing works of Michel Le Belhomme, who has dealt with imaginary space. And further inside, we will also have a small show of Arthur Bondar, who has worked with family albums, collected materials, and photographed them to build a chronology. And you were trying to create a certain kind of space with a certain kind of structure for it. Can you share a little bit on why you thought of that rather than putting the photographs up on existing walls?

SA: As that particular space will be the 1st room for the audience to walk through in Chobi Mela at Shilpokola, I wondered to myself, ‘how about we create a space to sort of push the mind to be ready for a new threshold?’ So as you walk into the space, it’s a photography show but you won’t be able to see any of the photographs at your first glance. One of the reasons why I wanted to do this is because just looking at a photograph in a photography show is so basic; that isn’t something I wanted to go with.

Also, in Michel’s work, his images are not just found images. In his work, he cultivates the images, he constructs them, then he photographs and then he shares them with us. So, my perception of his work is that he is trying to carve out a very fine line within the photography and the experience of photographs. That line is so fine that it needs to be looked at very carefully. And for that, I thought, ‘how about I create a sort of floating space within the given space and then insert the images within that floating space?’ So when you are looking at the image, you are just very focused; you are not distracted by anything else. All these images are to be reviewed as an experience without any distraction and for me it was important to look at Michel’s work like that.

And the wall in the center will showcase the Ukrainian photographer, Arthur Bondar. We’ve decided to present it horizontally. I think it’s a very unique way of looking at photographs. We usually expect the photograph to be hung on the wall when it comes to an exhibition. But when we extend it out of the wall and look at it horizontally while the scale is very intimate, it goes with Michel the whole experience.

MW: But talking in more practical terms, since you are an architect, you always work with bigger projects compared to what we do as individual photographers. And of course, we have very limited budgets. So can you expand a little bit on that? Practically, is it really difficult for you to work within those limitations?

SP: You know, limitation is often the key to answer many of the complex design issues. So I like limitations. I think it makes me focused on the given issue with a lot of intensity. Of course, if you have money and the budget is large, you have the luxury to think differently. In many ways, it can also show the audience a different platform. But that’s just for the talk for this particular event. The budget is tight and I know that. And what I did within the budget is no less of an experience than what I could have created if I were given a huge budget. Limitation can be a way out at times. It’s alright.

MW: Let’s talk about another work. You are also dealing with the work of this Indian photographer named Dinesh Abiram, who is working with salt prints, which is a special kind of printing process from the 19th Century. He wanted to show his photographs on a table. Now, we are developing a completely different kind of structure, which I hope will have a very different kind of sculptural look. How you are going to present that?

SP: Well, I didn’t deviate too much from Abiram’s original idea. I think his work has an embedded poetry in them with certain degrees of intimacy. The viewer has to be a part of that intimate journey that Abiram has proposed through his work. I certainly took a clue from there and I animated the mechanics of that dream machine knowing the crowd that’s going to come in to experience this Chobi Mela. And I hope the way we thought of the armature for the show, will bring in a new dimension to Abiram’s work. Because it’s somewhat stemming from his original idea but it has been pushed to a new level. So that it can handle the audience in a more unique way, I would say, but it is yet to be tested. I don’t know.

MW: When we generally speak of architecture, photography or performance art in different kinds of festivals such as the Venice Biennale, these are all linked. And for example, the Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei was the architect of the Olympic stadium. I think it is quiet fascinating now-a-days how in contemporary art, different art forms engaging with each other and having a conversation. Do you think that lacks in Bangladesh? Do you think there should be more conversations over different mediums from different group of people- from scientists to engineers to photographers to architects to painters?

SP: Absolutely! I think it’s way too late. In my own practice, I feel that there are all these different crowds among different architects. And why is that – I have no idea! I think, of course, we have our own gain through our own journey, but we need to look at it from a distance. I believe all of us in 2014/15 have a responsibility to leave something significant or important for those who are going to look back from the 2030. In this journey, an architect cannot take so much responsibility, a photographer cannot take his own responsibility; all of us have to chip in to actually express the much larger canvas of a society. So a photographer should do his/her share and an architect should do his/her share. But what we propose in the end is that whoever we are has to speak out of the thing that represents the society as a whole. And I think it is very unfortunate in many parts of the world, especially in Bangladesh, that we really somehow compartmentalize our everyday journey and we only look at things through our own sort of glasses, you know ?

MW: With our own rhetorics?

SP: Right. I think overlaps are exciting. So, overlaps must be there and it can only speak of things as a whole not as parts. You know, the universe is much larger than the world. So I would rather be a part of the universe than my own world.