Rupert Grey, media lawyer, photographer, adventurer, has been at every Chobi Mela since 2004, holding media law jam-sessions in Pathshala, exhibiting his photographs or delivering lectures on copyright in a digital age. He recalls the night he arrived in Dhaka for Chobi Mela IV, and reflects on fifteen years of attending the festival, alongside images drawn from his extensive archive produced during this time:

I arrived in Dhaka at midnight on December 5th 2006 and spent the rest of the night hanging a photographic exhibition which the authorities were desperate to close down. It was an appropriate start to a festival for which the theme was Resistance. The gallery, in the National Museum, was packed with young photographers who were not to be silenced. It was an exciting night. The images, curated by Robert Pledge, founder of Contact Press, were ground-breaking and moving. By breakfast – roti and chili omelettes at a street stall at dawn – the exhibition was up, and I realised that Chobi Mela was not just a festival; it was a campaign for freedom of speech, human rights and the righting of wrongs.

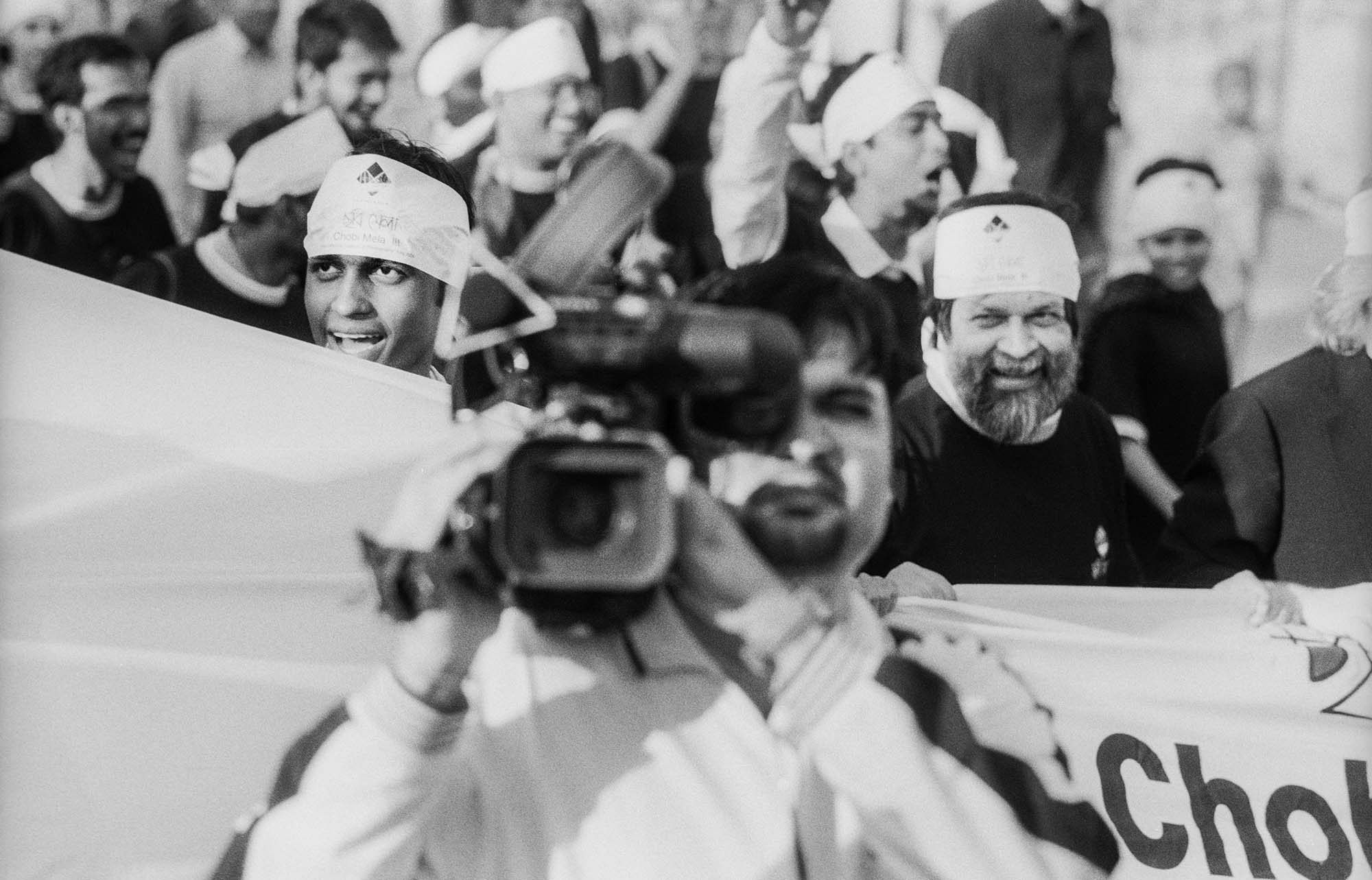

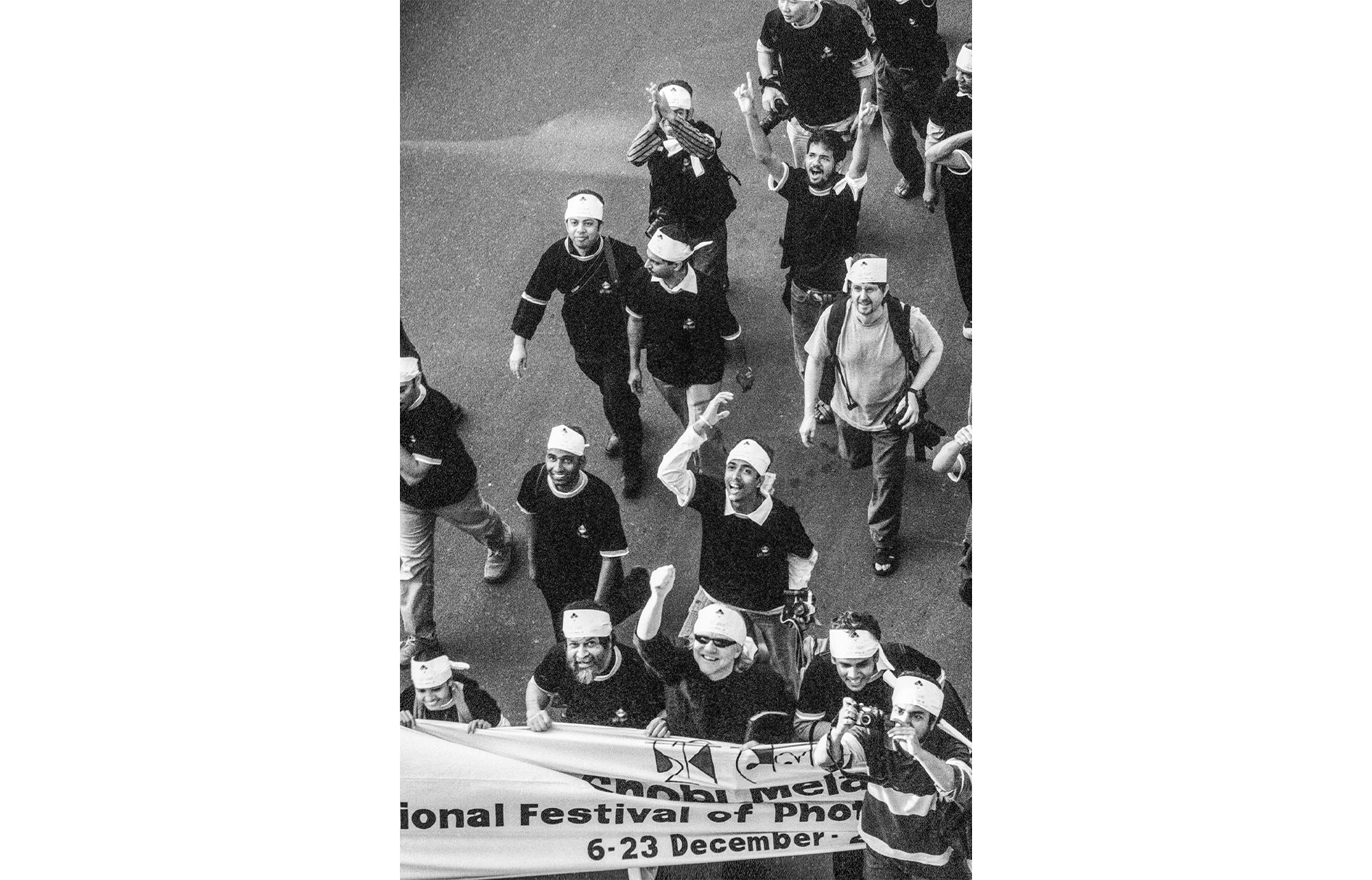

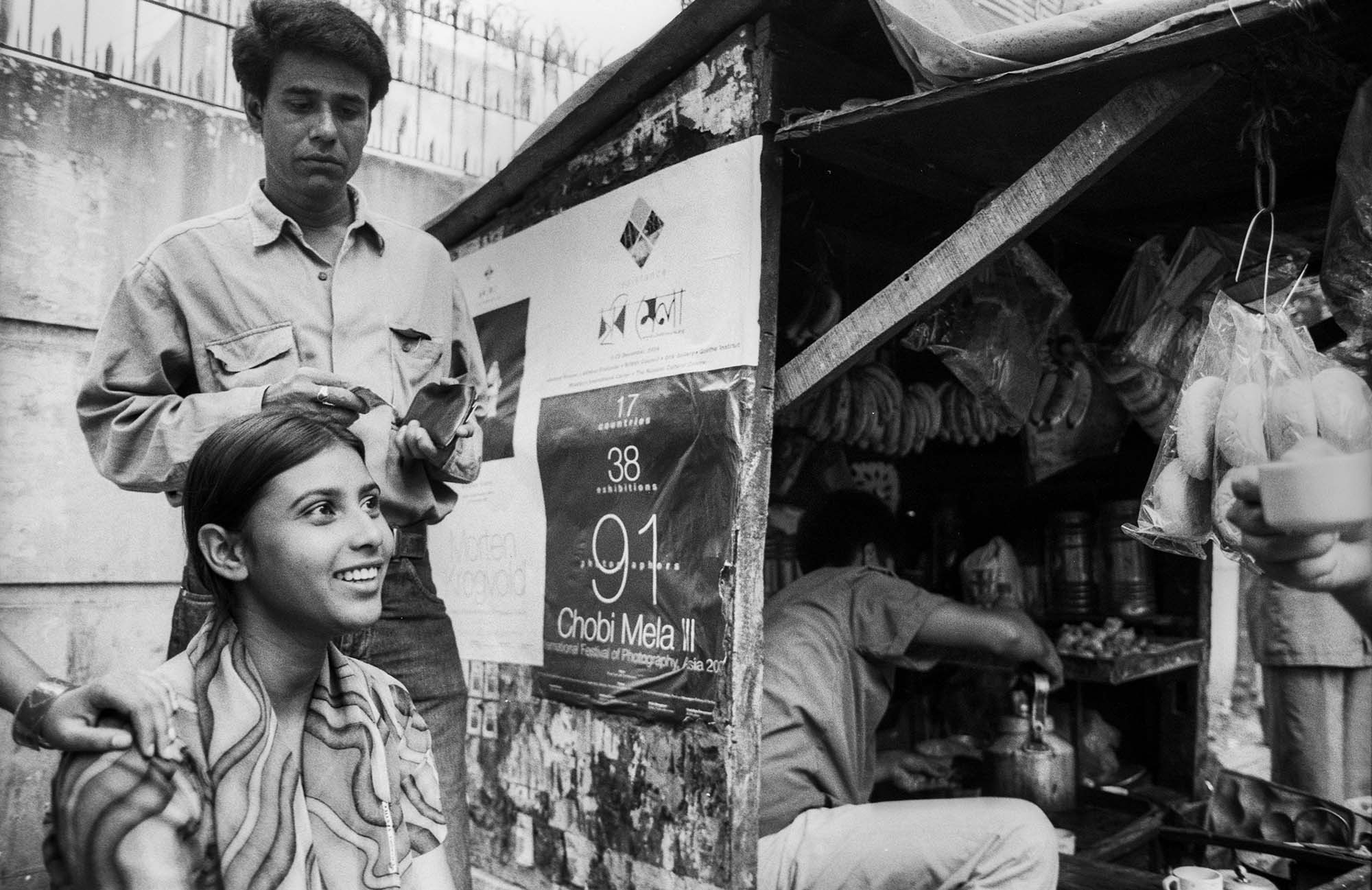

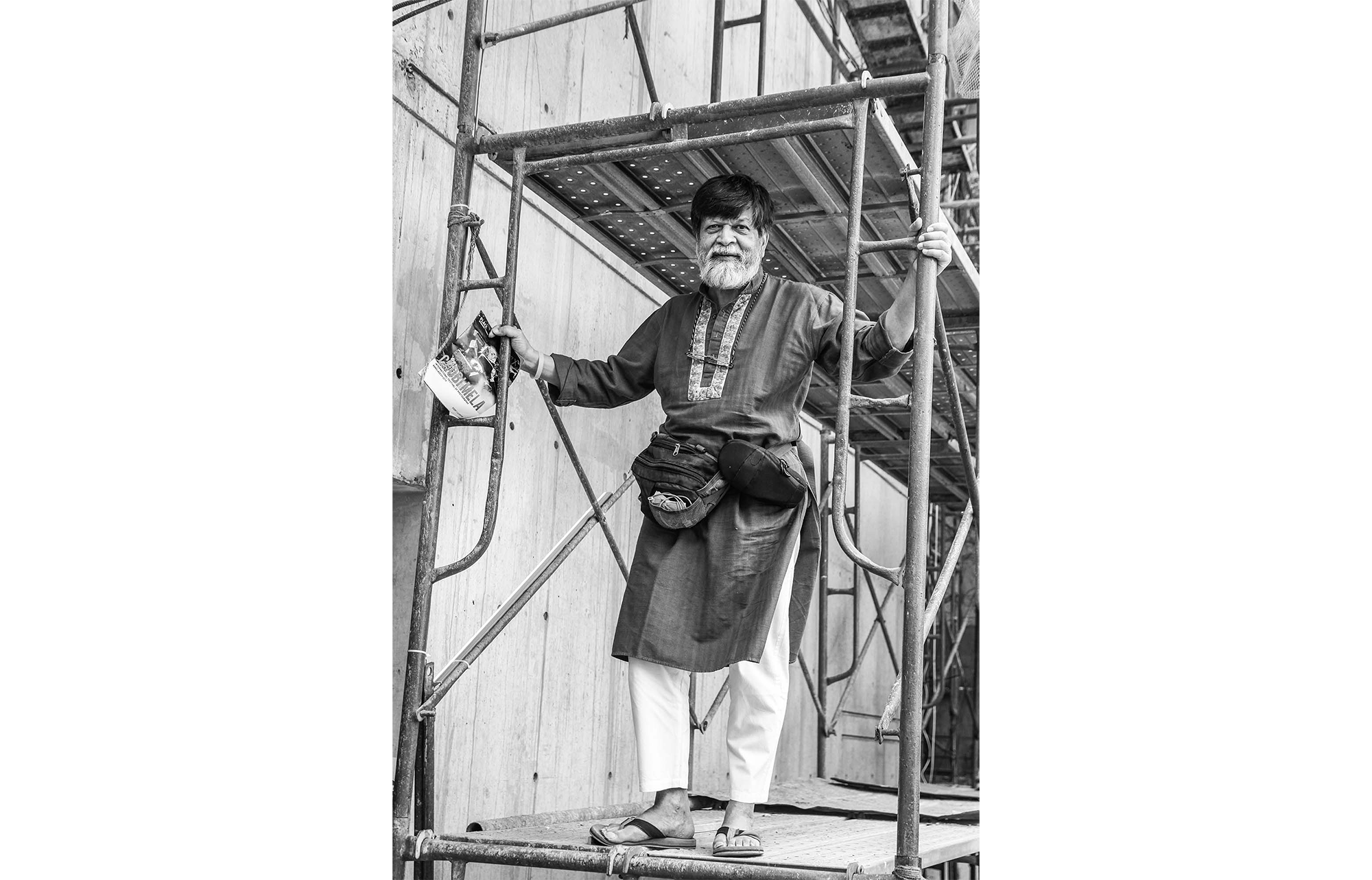

From there to the streets for the opening rally. Crowds gathered behind Chobi Mela banners, drummers and trumpeters drowned the noise of traffic, students sporting headbands danced and shouted. Here was an exuberance with serious intent, and at the head was Shahidul Alam, who I had l met in the Sundarbans twelve years before. It dawned on me that Chobi Mela was no mere campaign. It was a movement to change the landscape of photojournalism.

The question at the heart of the festival was what a camera is for. It is not simply a device for taking photographs. It is a non-violent and highly effective weapon for portraying injustice, recording oppression, and changing public opinion. In the right hands the camera could be, as Cartier-Bresson put it, a flamethrower. Rather like a good lawyer, it occurred to me.

At that time, I was a senior partner at one of Britain’s most prominent law firms. My area of practice was media law, and it was in that capacity that I had been invited to Bangladesh to give a public lecture on international copyright. I did not expect to find myself at the barricades in support of an unfamiliar but agreeably radical revolution. That moment was a turning point for me. After a week of copyright workshops and street-stall chats with students I realised that I was privileged to witness at close quarters the transformation of a community of young photo-journalists in a country which was barely on the map into an internationally recognised force.

As, many years later, I write this piece, the World Press Photo Exhibition 2022, the world’s most prestigious award-giving body, is opening in Dhaka. Tanzim Wahab, who chaired the Asian jury, was the second Bangladeshi to do so, following in the footsteps of Munem Wasif. Shahidul Alam was the first person to Chair the International Jury who was neither European nor American.

All three are from Drik, the agency which Shahidul and his colleagues founded in 1989 to provide Asian photographers with access to international media. It was the first platform in the developing world to challenge the dominance of western culture in the selection and interpretation of international news. No longer, was the plan, would Bangladesh be portrayed as nothing more than a series of catastrophes. Drik had become a hub for these young camera-wielding change-makers.

Over the next few years most of the world’s foremost curators and photojournalists came to see what was going on, drawn by new voices heralding changes in their field. They recognised, as I did, that the power of the western gatekeepers was slipping away with the arrival of digital technology. The West’s monopoly over storytelling was being challenged, both in the choice of photographer and control over dissemination.

Drik is always the first port of call when I arrive for Chobi Mela. It is the hub for exhibiting photographers just arrived in town wanting to know about their prints, for lecturers like me needing to know the programme, film-makers hoping to use the recording studio, journalists, sensing the eclectic magic of Chobi Mela, looking for a touchstone to ignite a story. It looks like chaos, but it is a chaos you want to be a part of, and out of it emerges powerful storytelling and a tangible sense of cohesion. It is this tension that marks Chobi Mela out from other festivals.

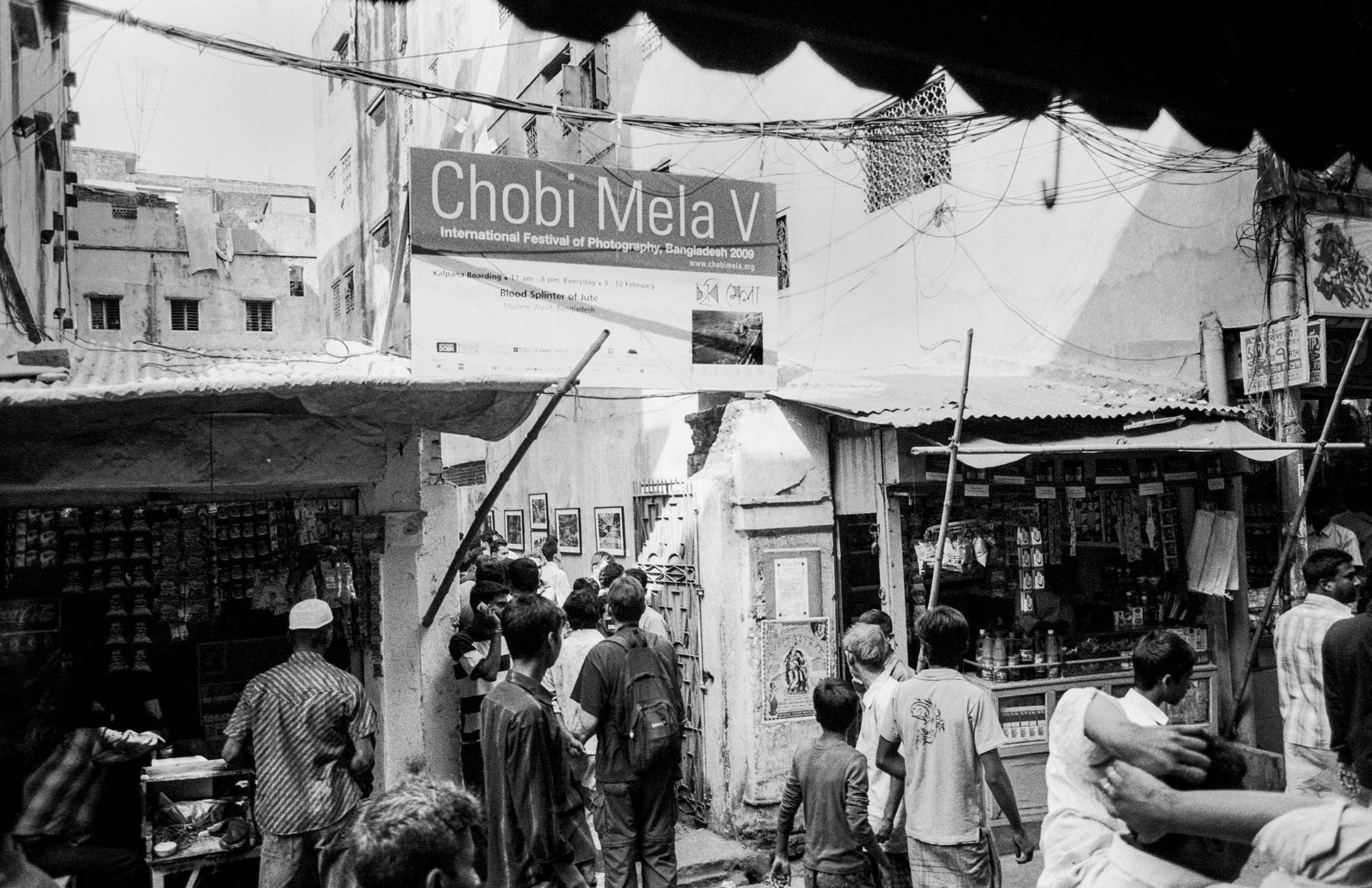

There is another critical distinction: it is no coincidence that political protest and the fight against injustice have been the underlying themes of Chobi Mela since it started in 2000. Freedom of speech in Bangladesh has to be fought for. Exhibitions have been closed, dissenters silenced, and public speakers cancelled. But always the Drik galleries have stayed open. Even when political protest in the streets brings Dhaka to a literal halt, the gallery doors remain open.

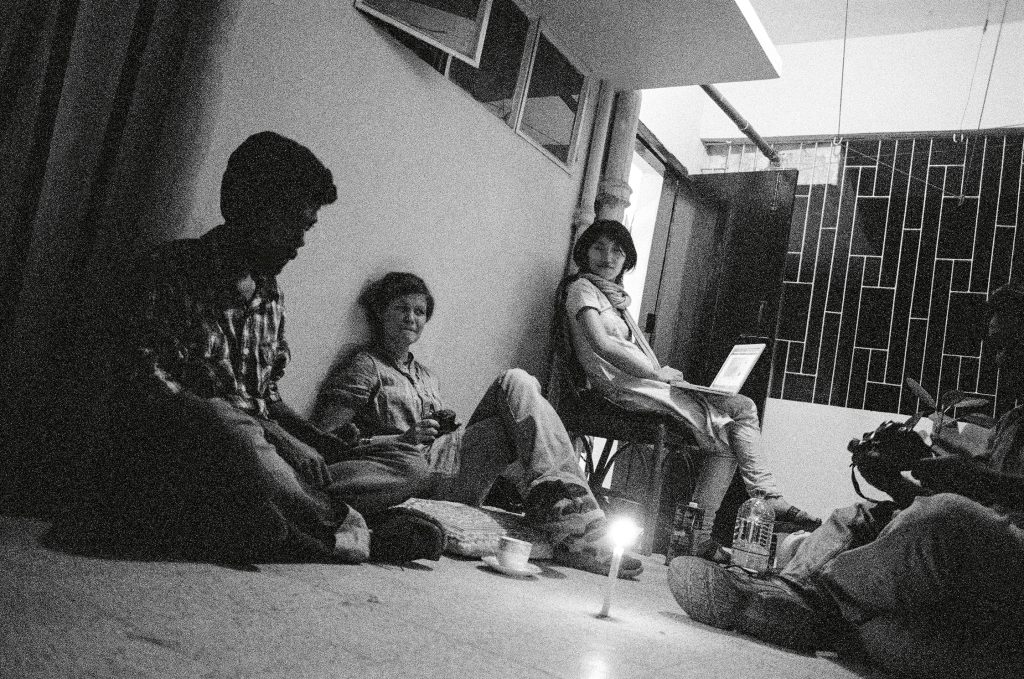

Shumon spoke of the influence of Ian Berry, who he regarded as the last surviving photographer of the golden age of Magnum; Maria from Norway, drawn here by Drik and Pathshala and the ideas they represent, and Christina, a Chinese Canadia who has been on the road for two years and believes that art is the way to bring peace to the world.

It was late and the conversation flowed easily. We shared our histories, a little something of our lives, and even our loves, not in an intimate way, but after the manner of travellers giving and taking and sharing the passing moment. There was amongst us an understanding that something was stirring here in Bangladesh which drew us in. Difficult to put a finger on it. It’s not Shahidul himself, but it is to do with his presence. He has, in Chobi Mela, lit a candle, one of us remarked, and we and others have come to see what it is that he is looking at; having seen it we realise that it is bigger than ourselves and we want to be a part of it. Journal entry, 18 February 2009.

The second port of call is Pathshala , the place of learning founded by Drik 25 years ago and now the foremost photography school in Asia. It attracts students and teachers from widely different backgrounds and countries . There, as at Drik, you might meet members of the Out of Focus group, whose foundations were laid, in a literal sense, at the traffic-lights of Dhaka where street-kids sold flowers to drivers. I first heard about this group in 2004 while driving to Old Dhaka with Shahidul. A girl came to the window while we were waiting at the lights. Shahidul bought the flowers and they carried on talking as they waited for the lights to change. I couldn’t follow the conversation, but it was clear they were acquainted. I remarked on this as we drove on and the story unfolded.

Back in the nineties, during the dying moments of the analogue era, Shahidul gave a couple of kids point-and-shoot cameras with one roll of film while he waited for the lights to turn green. The catch was that they had to come to his darkroom to develop the film. It caught on. He set up a darkroom nearby, gave them a regular supply of film, took them on outings and paid for their schooling. Some of those street kids, male and female, are now leading international photographers.

In 2011 I spent a morning with Shahidul in Pathshala interviewing applicants for a scholarship from the Magnum Foundation. On the brick walls of the classroom hung powerful images and statements of purpose, revealing what young Bangladeshis minded about: exposing corruption, freeing children from slavery and women from violence. We awarded the scholarship to Taslima Akhter, a female student in her last year at Pathshala.

Two years later she took the image which became known as “a final embrace” after the collapse of the garment factory in Dhaka in which a thousand garment workers died. It won a World Press Photo award and was one of Time magazine’s top 10 photos of 2013. It also delivered a high voltage worldwide shock to the garment industry.

The vision which Shahidul shared with me on the scrubbed decks of the King’s boat in the Sundarbans thirty years ago has become reality.

This text has been adapted from Rupert Grey’s 2023 book Homage to Bangladesh: A Memoir of a Time and a Place, published by Unicorn Books in the UK. Plans to publish it in Bangladesh are in hand.