Graciela Iturbide (born 1942) is a Mexican photographer who turned to photography after the death of her daughter in the early 1970s. Munem Wasif, curator of Chobi Mela interviewed Iturbide in February 2013 when she came to Dhaka to receive Chobi Mela VII’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

Munem Wasif: I’ve been trying to understand your work for a long time because I want to write about it. And yet it’s so difficult because your photography is not about facts and there is so much poetry and mystery in your work. So I’d like to ask you, could you explain who is Graciela Iturbide? What is her work about?

Graciela Iturbide: I am Graciela Iturbide. I was born in Mexico. My father was a photographer. He always took photographs of our brothers and sisters and we were 13 altogether. I loved to steal the photographs from where he would keep them. I actually wanted to become a writer and I wanted to study philosophy. But I come from a very conservative background, so I wasn’t allowed to do that. What I essentially look for everywhere is poetry, be it in literature, be it music… So, who is Graciela Iturbide? I don’t know, I still don’t know. I am still searching for her. But I love poetry, be it in music or be it in Andrei Tarkovsky, Francesca Woodman or anyone else, I just love poetry.

MW: You got married in your 20s. Was it normal in Mexico to get married at such an young age back then or were you completely in love?

Graciela: In my generation it was tradition to get married this young but I was also very much in love.

MW: You had three children in three years. When your six-year old daughter died, did that make a big impact on you?

Graciela: Obviously it was a terrible thing to happen in my life. That I lost my child. But at the same time it was just the moment when I started doing photography. So I feel that photography was also a sort of therapy for me.

MW: How did you meet Manuel Álvarez Bravo? What was it like to work with him?

Graciela: When I went to study at the university he was teaching at the university as well and I attended one of his courses; that’s how I got to know him. Then, after a couple of weeks I became his assistant. At that time he was not that famous in Mexico, he was very famous in Europe and the United States. He was known in Mexico but he was not really a big star. So, what I really need to make clear is that he was not just a teacher of photography; he was a teacher about life for me. Because he taught me about everything, he talked about literature, cinematography…so he was more of a teacher of life…he never said this picture is good or this picture is bad, he would never say that flat out. Instead, he would always say something to guide you in the right direction. Yet he would never say, “This is good or this is bad”.

With Álvarez I went to certain little towns but I was only his assistant for two years. After that I made the decision to cut the umbilical cord and make my own way.

MW: How did you decide that you wanted to work on Juchitán – that community, what really attracted you?

Graciela: The person who got the project rolling was Francisco Toledo, a very important Mexican painter. He was born in Juchitán. He actually asked me to do the project and the idea was for me to take pictures of the town and then bring those pictures to the town and show them at the Casa de la Cultura in Juchitán. That was the original idea. But later I kept on going to the town and that’s how the book I did about Juchitán came about.

MW: For me there is a certain kind of mystery that I see in your work. The way you frame things, your inclusion of animals, there’s a certain kind of poetry you have in your pictures. How did you develop that style, was it very spontaneous or is there something that influenced you?

Graciela: I did not really consciously develop a style. The style that I have comes from within me. Of course I have been influenced by many photographers in a positive way but I do not feel that they influenced my style itself. That one, as I said already, is very intuitive, it comes from within me. It’s also what Alvarez Bravo said – that photography is basically everything that surrounds you, everything that surrounds you influences you, what you read, what you see… So the style is very me; from within me.View fullsizeView fullsizeView fullsizeView fullsize

MW: Are there are any particular photographers that you really admire?

Graciela: Koudelka, Josef Koudelka. He influenced me a lot and he is also my friend. I love his photography. Francesca, I am familiar with her work only for the last fifteen years. I love what she did, but there is not really a connection between her and my work.

MW: Why do you love Koudelka’s work? Is it because there is a bohemian quality in his work or is there any certain thing that you love about Koudelka?

Graciela: I love the person because he is very free and his work because it is so poetic, it’s like poetry.

MW: When I look at your early work, especially photo poche book, which is one of my favourites, in a lot of pictures, it’s more about humans and you are very close, intimate to your subjects. There are different kinds of animals; different kinds of relationships between man and nature. But in your latest work, it’s more about nature but I can still see Graciela Iturbide – the poetry is still there. It is a bit more distant but at the same time it has that obscure and mysterious quality. Yet it has no humans in it, it’s about landscapes, its about spaces. Why have you shifted your lens from humans and animals to nature?

Graciela: First of all you need to try new things and second of all because I now tend to travel a lot. My pictures are a sort of travel diary, for example these pictures are from Italy. As an artist you need to move on, you need to try new things. I can’t take pictures of Juchitán and Juchitán over and over again. And in the end, photography for me is just an excuse to get to know the world.View fullsizeView fullsizeView fullsize

MW: This is really interesting to me, because in Koudelka’s work as well there’s been a shift from human stories to landscapes, Koudelka shifted to the panoramic, produced chaos; you have also shifted in this direction.

Graciela: Concerning Koudelka, yes, I have noticed the change as well. Once I actually wanted to do a project on gypsies but then I saw the work he had done on gypsies. So I said to myself, well, a great photographer already made a project on this subject so there’s no need for me to do it. But generally speaking, the shift I made from the personal to landscapes – it was a very slow and gradual process. For example, here in Dhaka I’m finding myself taking a lot of portraits. Because they establish a certain complicity with the people and simply because of the fact that people are also very happy when I take pictures of them. So in Dhaka that’s what I like to do. I have done a lot of portraits. But I also took some shots of urban landscapes.

MW: I don’t feel like photographing when I’m in Europe, when I’m travelling. You have travelled to many places, to Africa, India and lot of different countries. Do you feel the same connection there as you feel with Mexico?

Graciela: Obviously it’s a different kind of connection; Mexico is different compared to other places. When I went to Rome I got invited to Italy to make a book about the city and I had an instant connection to the city. Especially the south of Italy which is very similar to Mexico in many ways. On the other hand I’ve travelled many times to Paris and I never really take pictures there, I mean I take pictures but they are not good. Of course there are many different ways to connect to a place. As I said before when I travel and take pictures I need to also live with the people. I need to have that connection with the people. It’s a different thing taking pictures when I am in Mexico, of course.

When you are an artist or a photographer you always need to establish a connection to the place where you are. If you are a writer and you are in Rome you will have a specific connection to it, then perhaps you will go to Sweden and you will have a different connection and it will be a very different experience. As with me, maybe you go to Paris and nothing happens, it doesn’t really work for you. But you always need to try to connect to the place where you are. View fullsizeView fullsize

MW: In your early work there are many depictions of festivities and celebrations but on the other hand there is a sense of death and sadness. Both are somehow growing together. Did you mean to portray that?

Graciela: In Mexico in general people are afraid of death but they also like to play with the theme of death. So there are many, many festivals, such as the one on 2nd November, which is the Day of the Dead. Or on other days when it is a feast day of a saint, people will take food to the cemetery, sing songs and maybe even take a piano to the cemetery and play there. In Mexican culture people are afraid of death, that’s why they try to attack it straight on, so they play with it, they try to make light of it. So perhaps that’s what you see in the pictures.

On the Day of the Dead, on the second of November, it is custom to eat skulls made out of sugar. I would get you a skull with you name on it and give it to you as a gift. And then you would eat it. On that day people also put up an altar in their houses where they put the skulls, maybe even little skeletons – like toy skeletons and flowers that one usually sees in cemeteries. So death is painful but it is also a celebration.

MW: You say you were always travelling by yourself during that time. How did you manage to develop your films, make your prints when you were travelling during that early phase?

Graciela: Yes, I would usually travel by myself except in the beginning. Sometimes to the towns nearby I would go with Álvarez Bravo but otherwise I would travel by myself and what I would do is just take pictures. Then, back in Mexico City I would make my own prints. Even when I went to Juchitán, I went by myself. It was an 11-hour drive; I drove my own car and went myself. In those cities, in those towns, the people would take care of me and I would usually stay with them.

MW: So who was taking care of your children during those times?

Graciela: Their father. (little smile)

MW: Oh! You weren’t divorced by that time?

Graciela: Yes. But he is also their dad. But sometimes the children even travelled with me. They are very proud that I am a photographer since they were very little.

MW: Do you have a dark room in your house?

Graciela: Right now, no, but up until two years ago I had one. The past two years I do not have a dark room in my home because I’m travelling a lot and there are two people who are helping me take care of that now.

MW: How did you survive doing these projects? Did you have money or did you need to do some assignments?

Graciela: I was very poor(smiling).

MW: But a lot of people say that you came from a very rich family.

Graciela: When I got divorced my family no longer wanted to help me financially. They also didn’t like the fact that I was a photographer.

MW: Were there any other female photographers during that period working in Mexico or were you one of a few?

Graciela: In Mexico there were some other female photographers. Tina Modotti, Lola Álvarez Bravo. But usually they didn’t come from my social background or from the kind of family I was from.

MW: You were invited by the Frida Kahlo museum to photograph her bathroom and nobody had entered that place for 50 years, how was that experience ?

Graciela: The director of the museum is a friend of mine. She invited me, actually she wanted me to take pictures of Frida Kahlo’s clothes. But I am not a fashion photographer so I was not very interested in that. Diego Riviera prohibited people to enter the bathroom for 15 years, but it remained closed for over 50 years in the end. So what happened when I entered the bathroom after 50 years? It was amazing. Of course, the smell was terrible since everything had been closed for 50 years. Then I started my work, very intuitively, I was just picking up different things lying around -the corset, the animals, the political pictures, such as that of Lenin… I just picked and chose …I just took pictures of that.

The thing which impressed me the most were the big bottles of Demerol, the painkillers, that Frida used in 30s. Frida Kahlo only died in 1954 but here in the bathroom one could still see the medicine she took in 30s. Also the powder she used. That was too strong for me of an experience; I didn’t take pictures of that, because that was powder which she used on her own skin… Essentially, the bathroom to me is a manifestation of the pain of Frida Kahlo.

MW: I’ve seen some of your colour photographs, which surprised me. I haven’t seen any of your other work in colour. Why did you choose to shoot in colour for that specific project?

Graciela: I tend to prefer to take photographs in black & white. It seems more mysterious to me. When I take pictures, I see things in black and white. I just remove the colours in my mind. The pictures you mentioned, I took on behalf of the museum; they had asked me to do some pictures in colour. One can see them in a gallery in L.A, the portfolio has about 8 pictures. Once I even did a book in colour. Generally I prefer black and white though, I feel that it gives you more possibilities. I do like colour photography though, such as the work of Rio Branco.

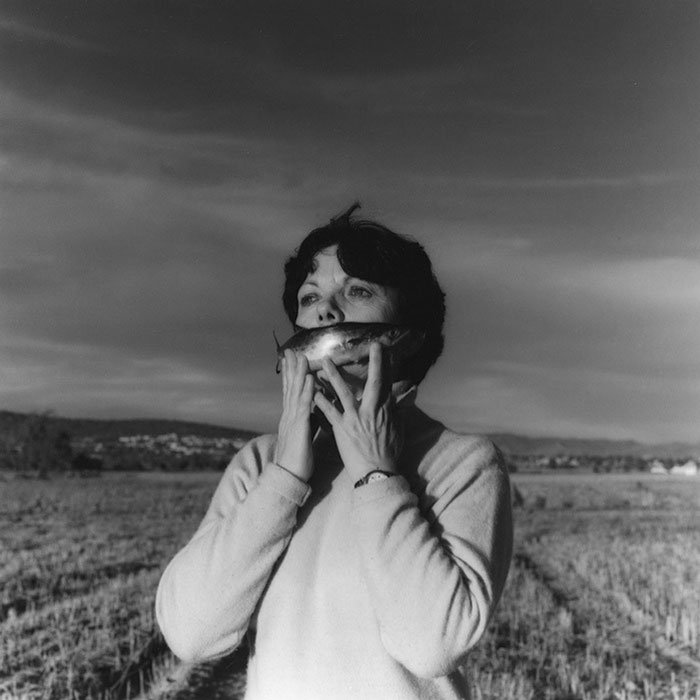

MW: It seems to me that you have a special relationship with animals, birds, fish, etc. I love your self-portraits where you are holding a bird or a fish. Why do you use animals in your photographs?

Graciela: It’s connected to my travels through Mexico. In the different towns and cities where I went to, people there tended to live with animals. So it came very naturally to me to to capture the animals with my camera. People would have cats, dogs and maybe goats and other animals. In my self-portraits it depends. The one you showed I took when I got separated from somebody and the caption is actually ‘Eyes to Fly?’. It’s more of a question, I placed the birds on my eyes and I asked myself, can I use these eyes to fly?

MW: So there is this one photograph of yours that I’ve been looking at over and over again. It depicts a man holding a fish, smelling the fish, looking straight ahead and his belt is unbuckled.

Graciela: The man in the photograph is actually my son, ha ha… (Laughter)

MW: Oh! To me it’s a very sensual picture and yet also very strange. I don’t quite understand what is happening but I just love it. Maybe you can tell a little bit more about the story behind the picture.

Graciela: I was traveling with my son when we stopped in this town and I bought this fish. What I wanted was to have a picture of me with the fish, and I wanted my son to take it. To see how it would turn out out I asked my son to pose with the fish first. Maybe it was after a meal and that’s why the belt was unbuckled. Anyway, I liked the picture but it was actually to see how I would look. Why the fish? Only Freud could tell!

MW: Before we end. I looked at your self-portraits very closely. You were so beautiful and you still are – so, tell me honestly, how many men have fallen in love with you ?

Graciela: (Laughter) Ha ha ha…I’ve had many partners, but because I really like love. Now I am alone because I want to be alone.

Discover more of Graciela’s work on her website: www.gracielaiturbide.org

All photos in this blogpost are copyrighted by Graciela Iturbide.