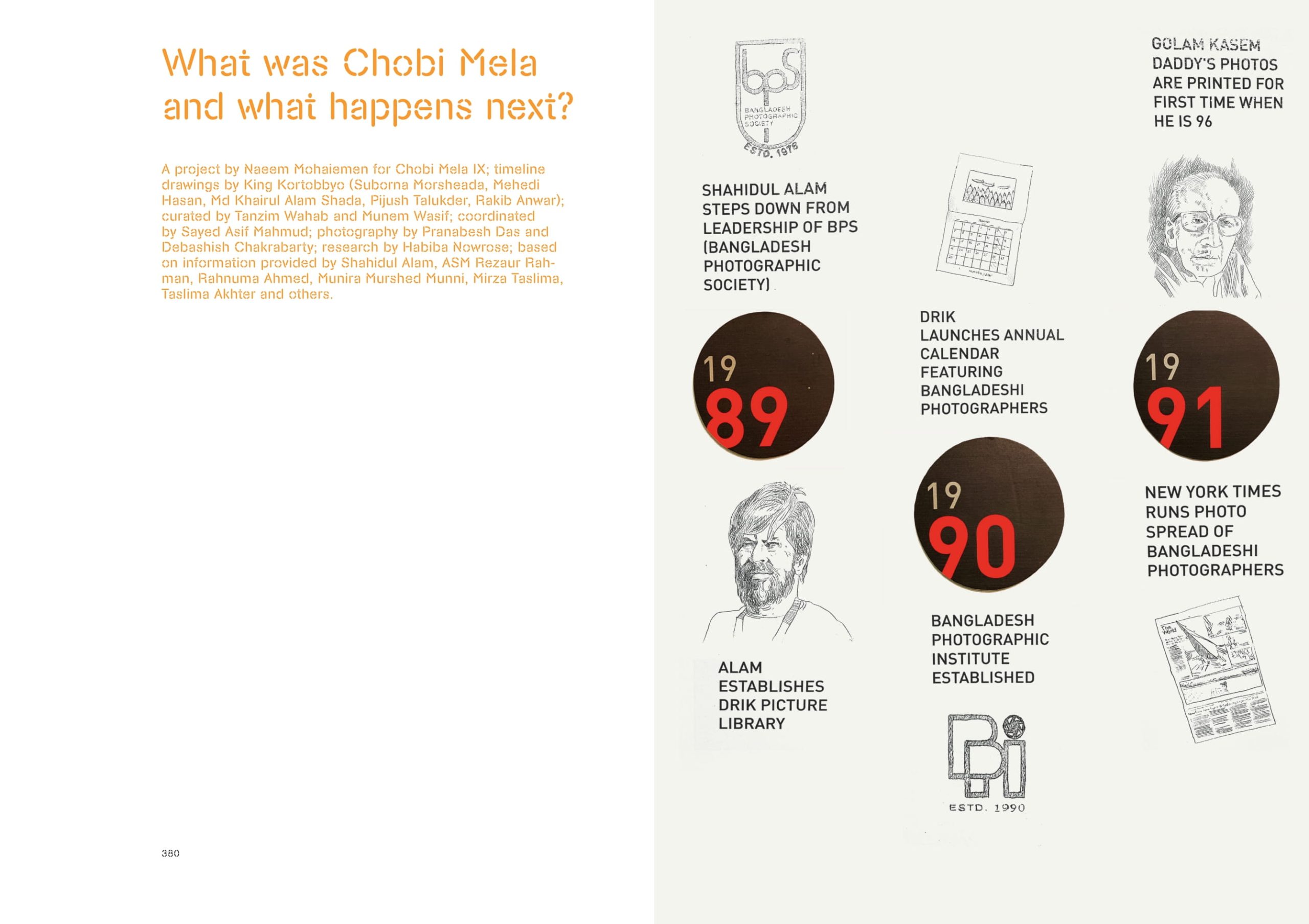

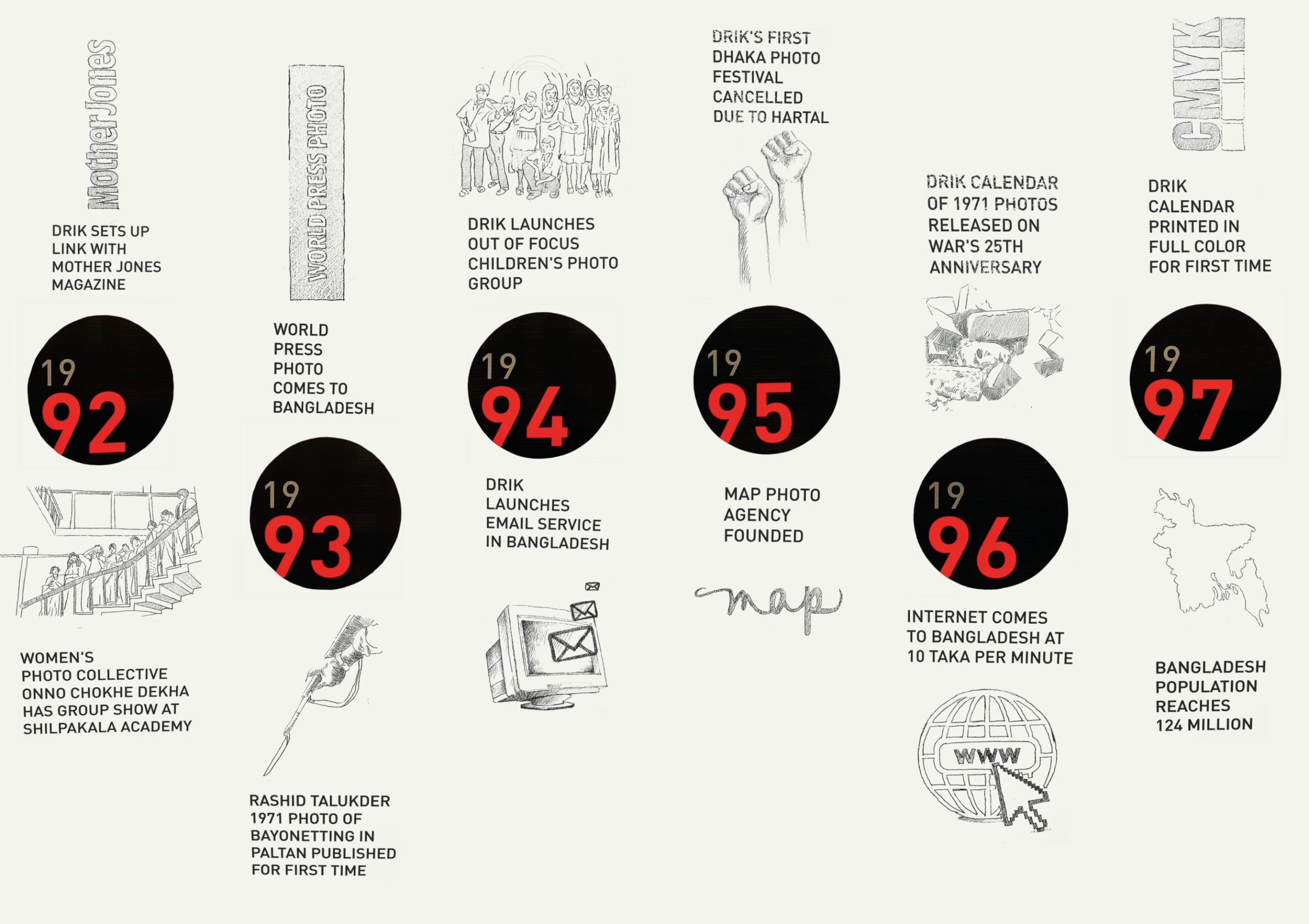

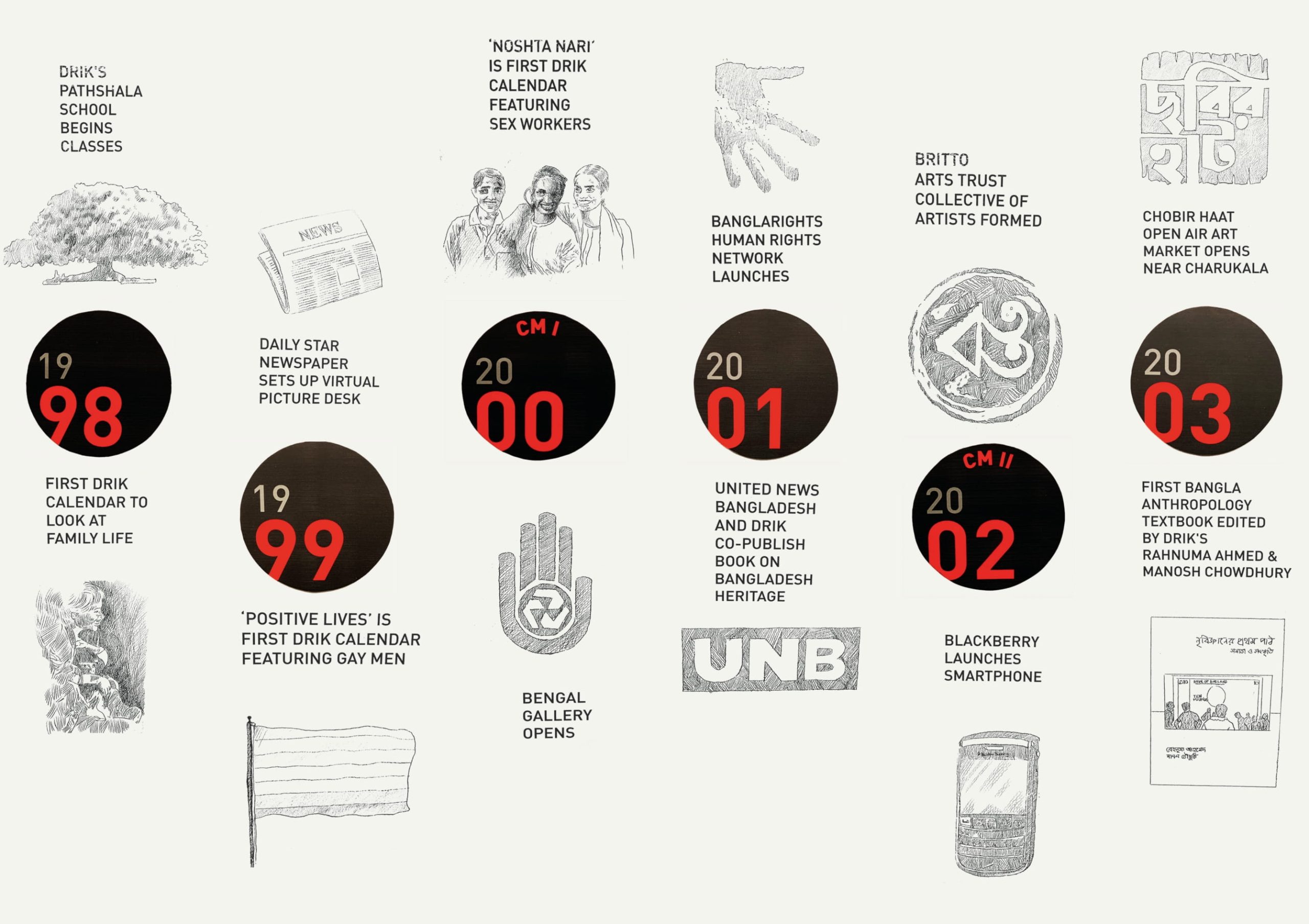

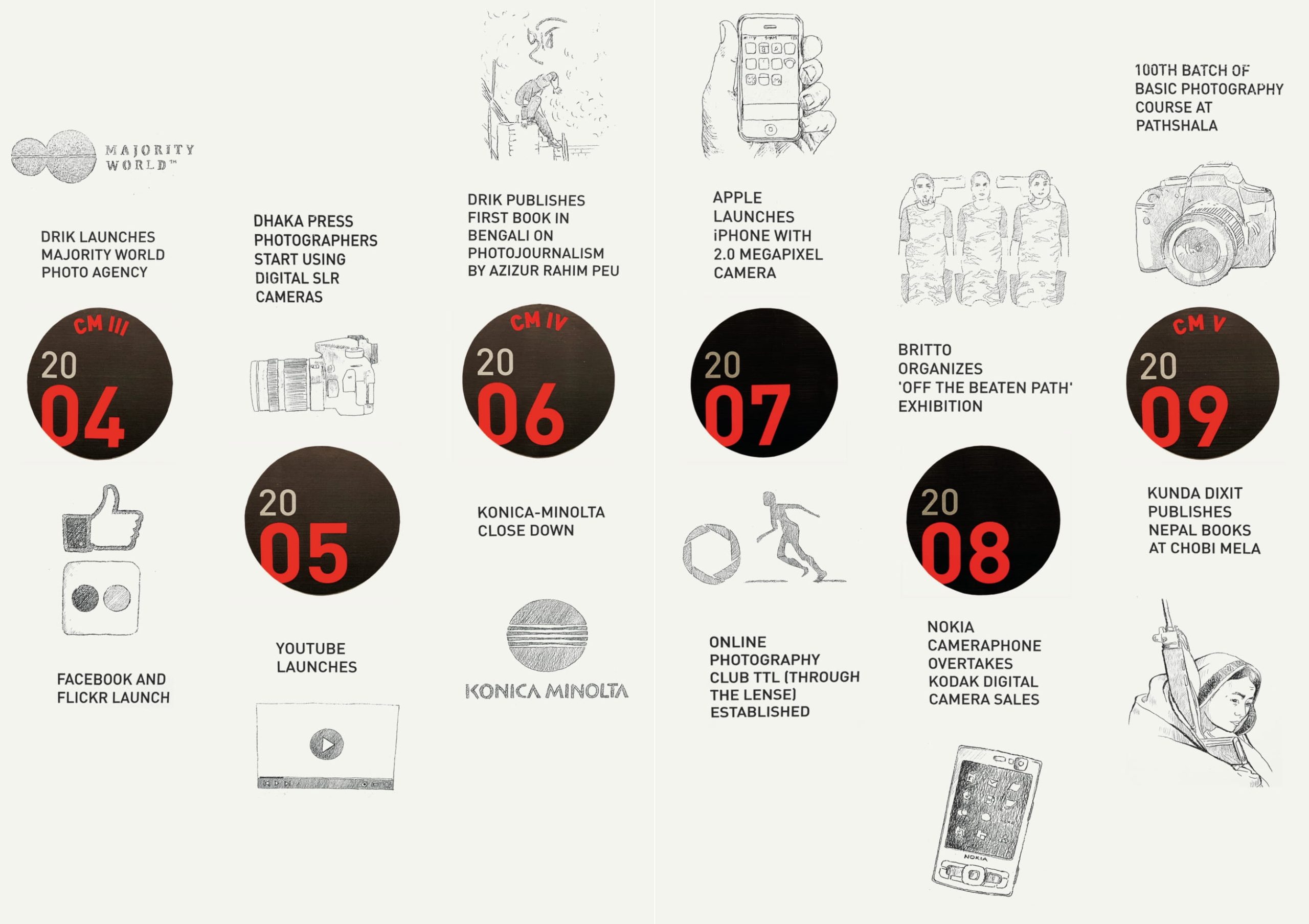

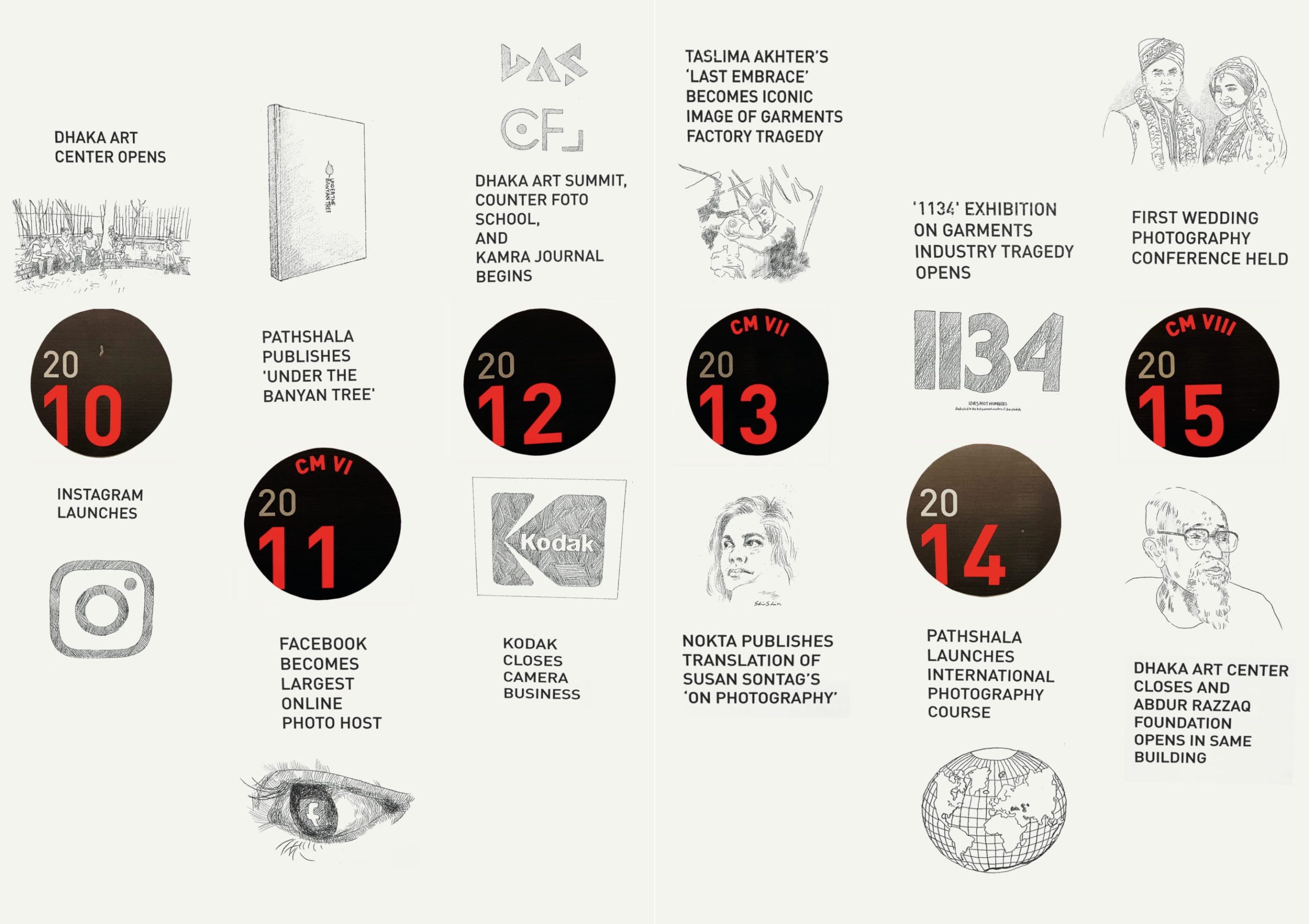

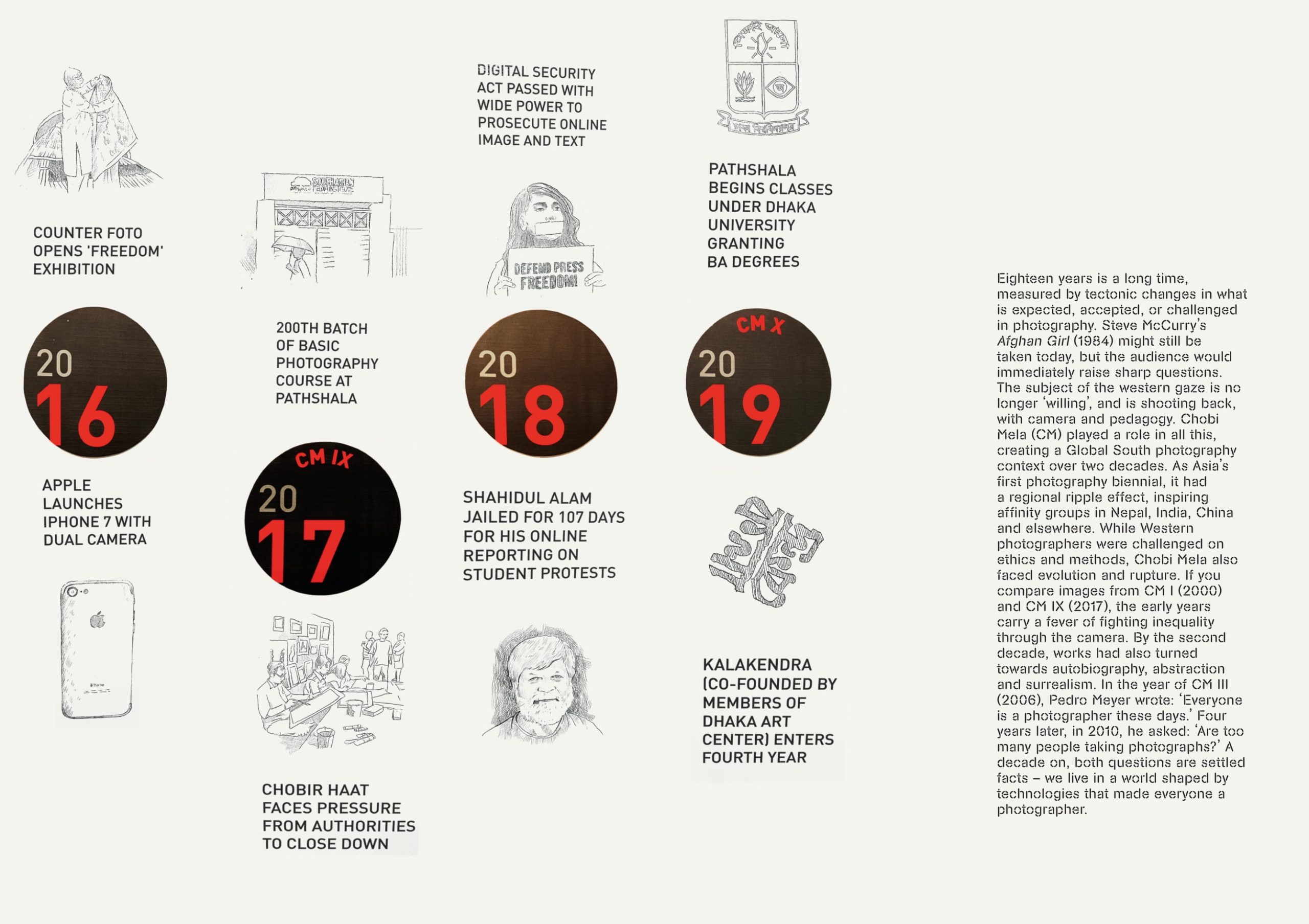

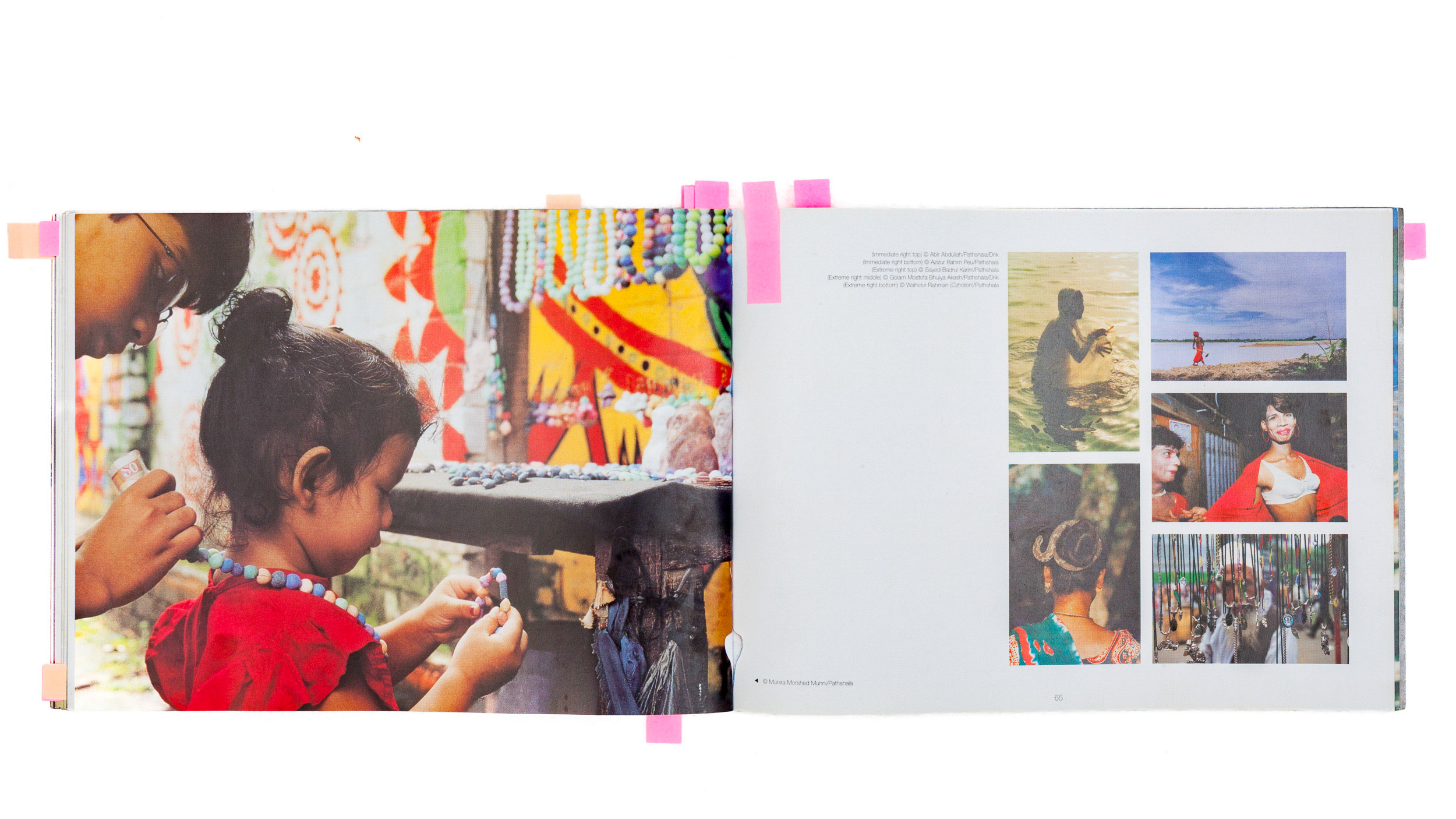

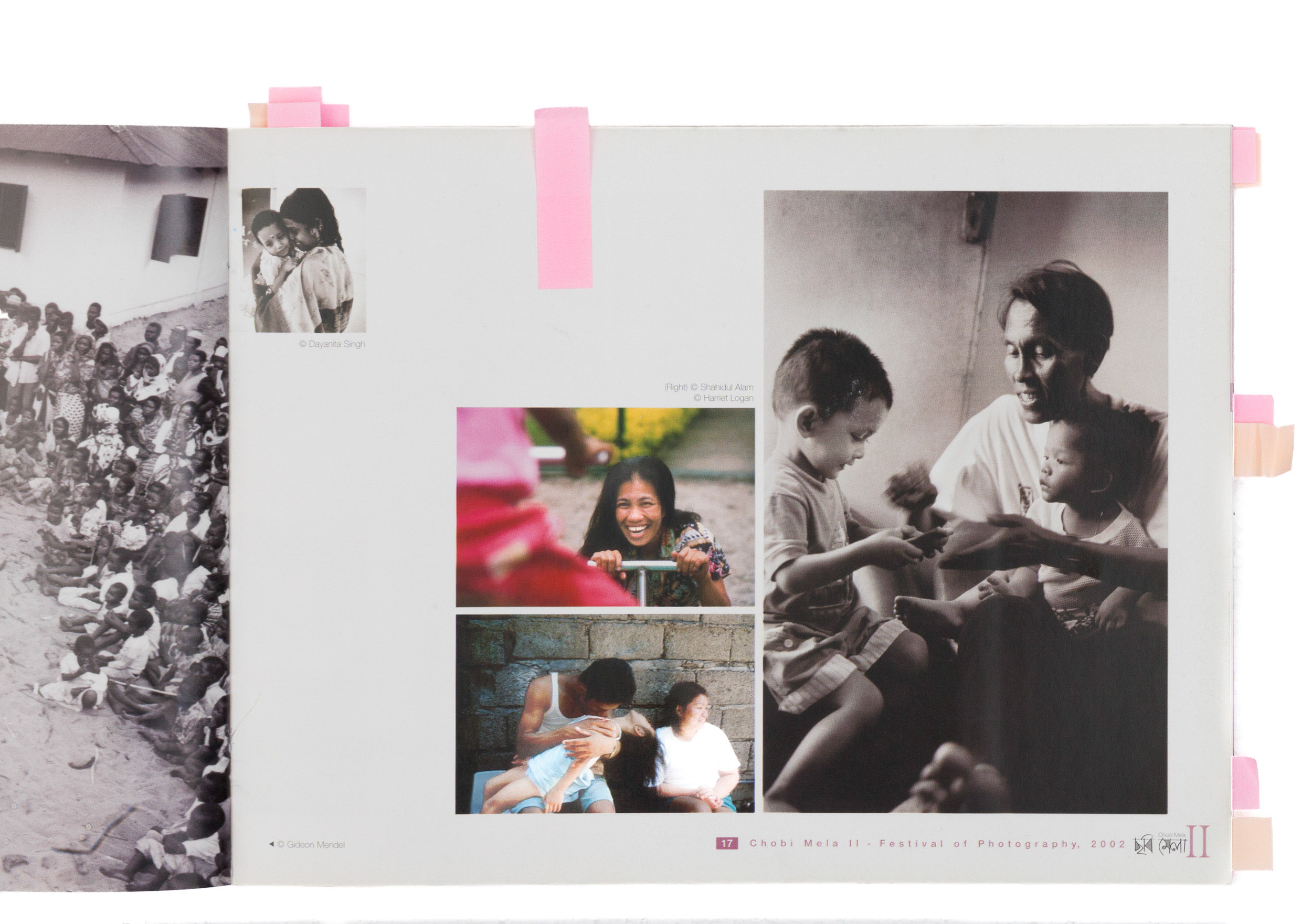

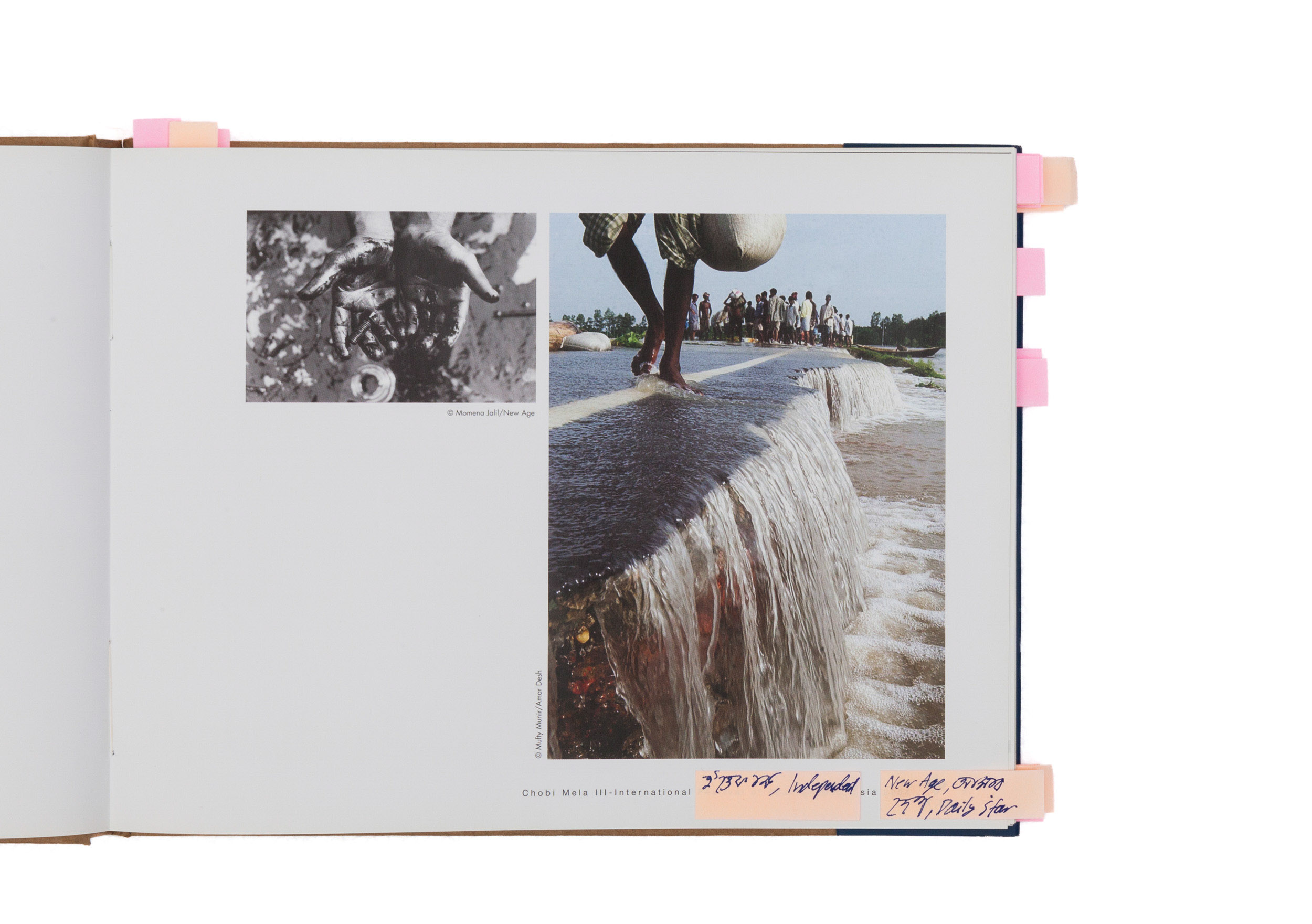

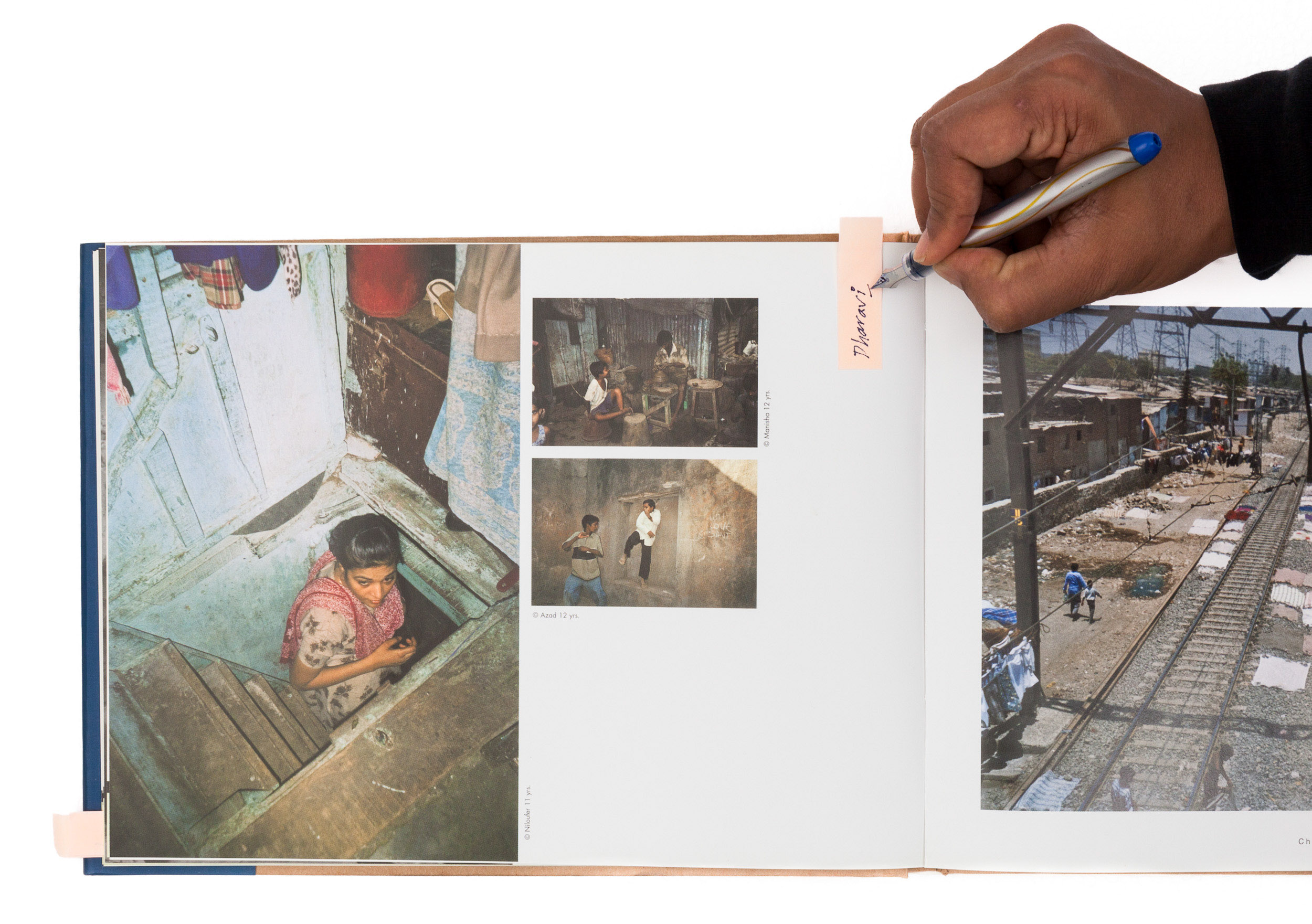

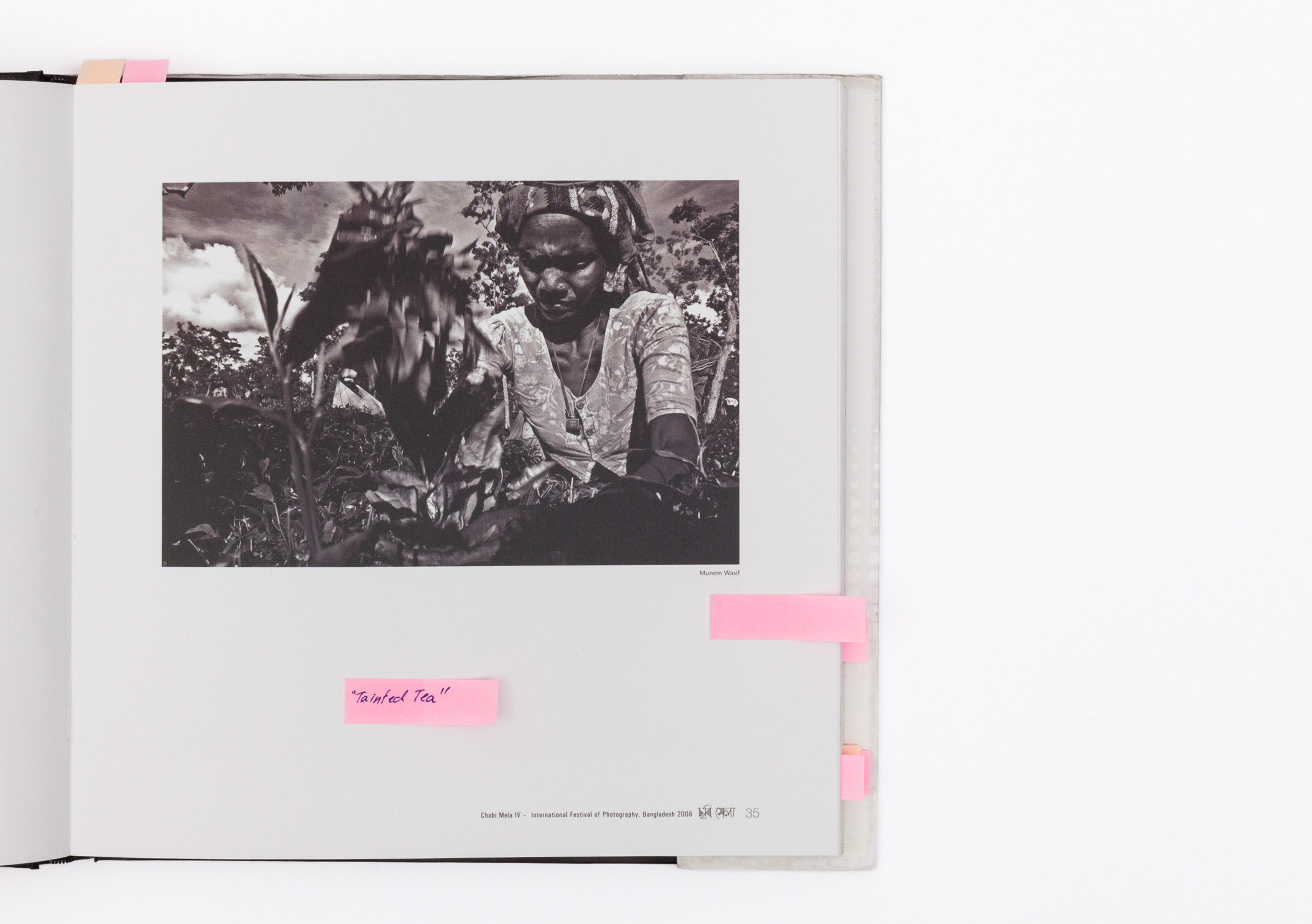

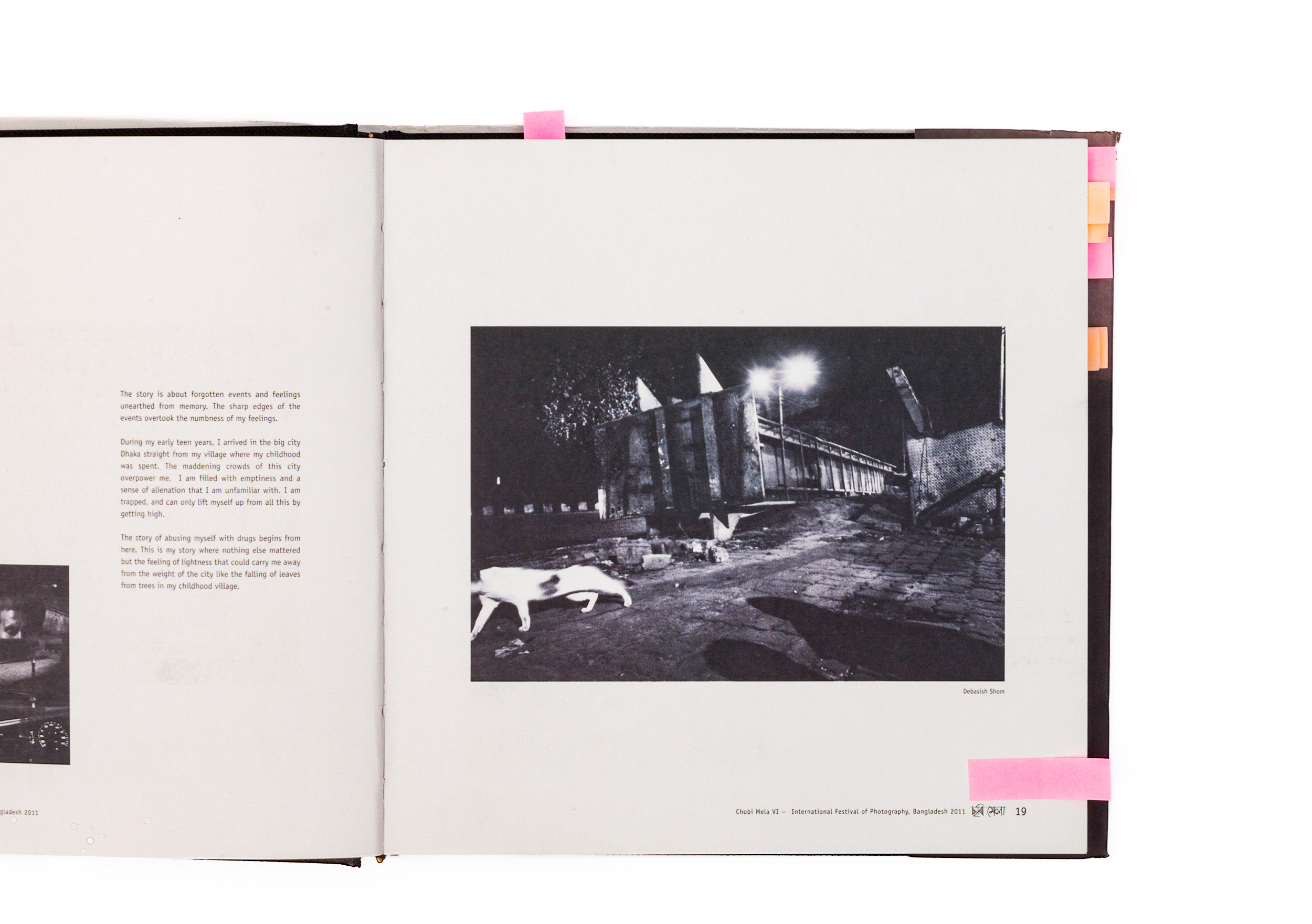

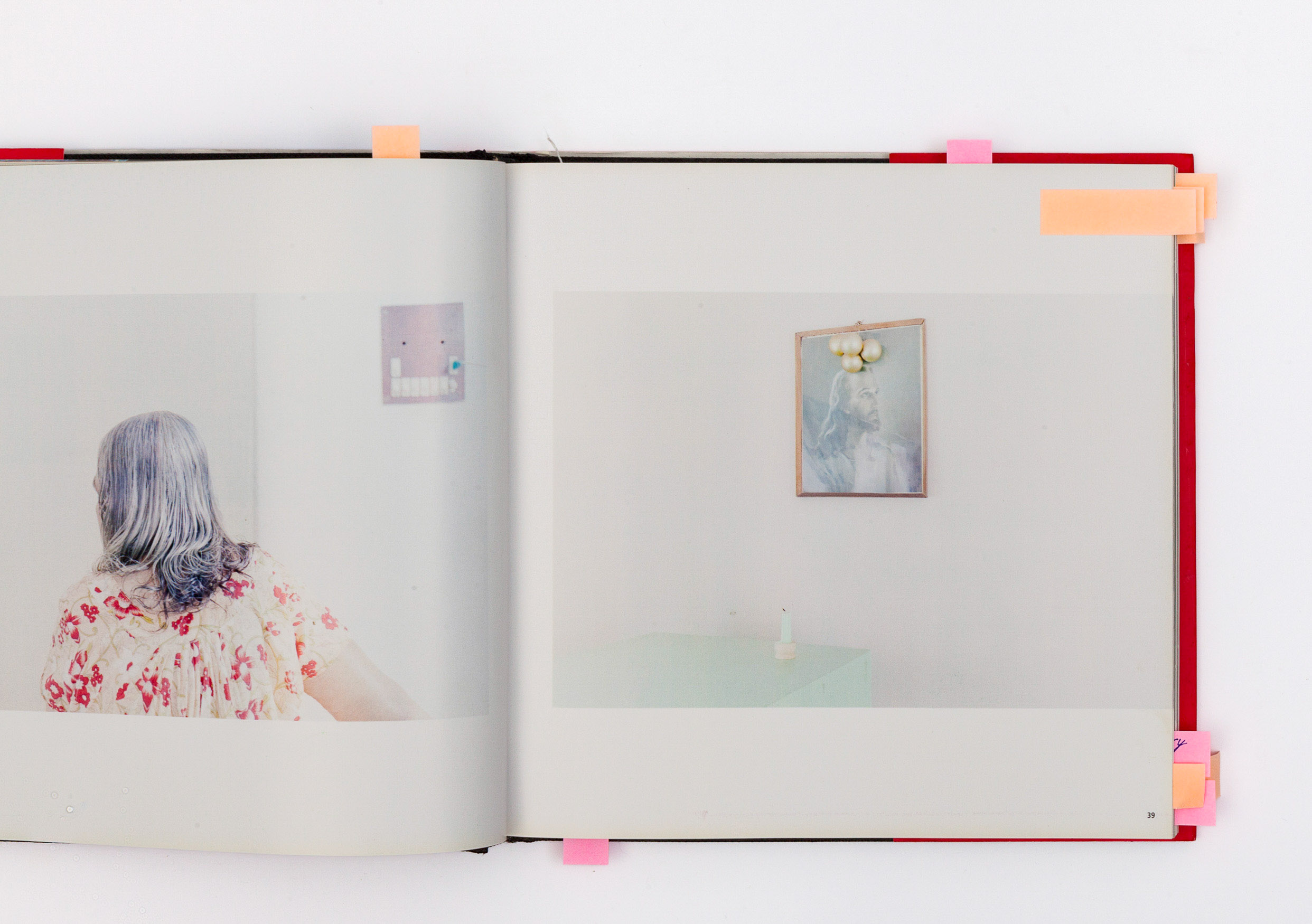

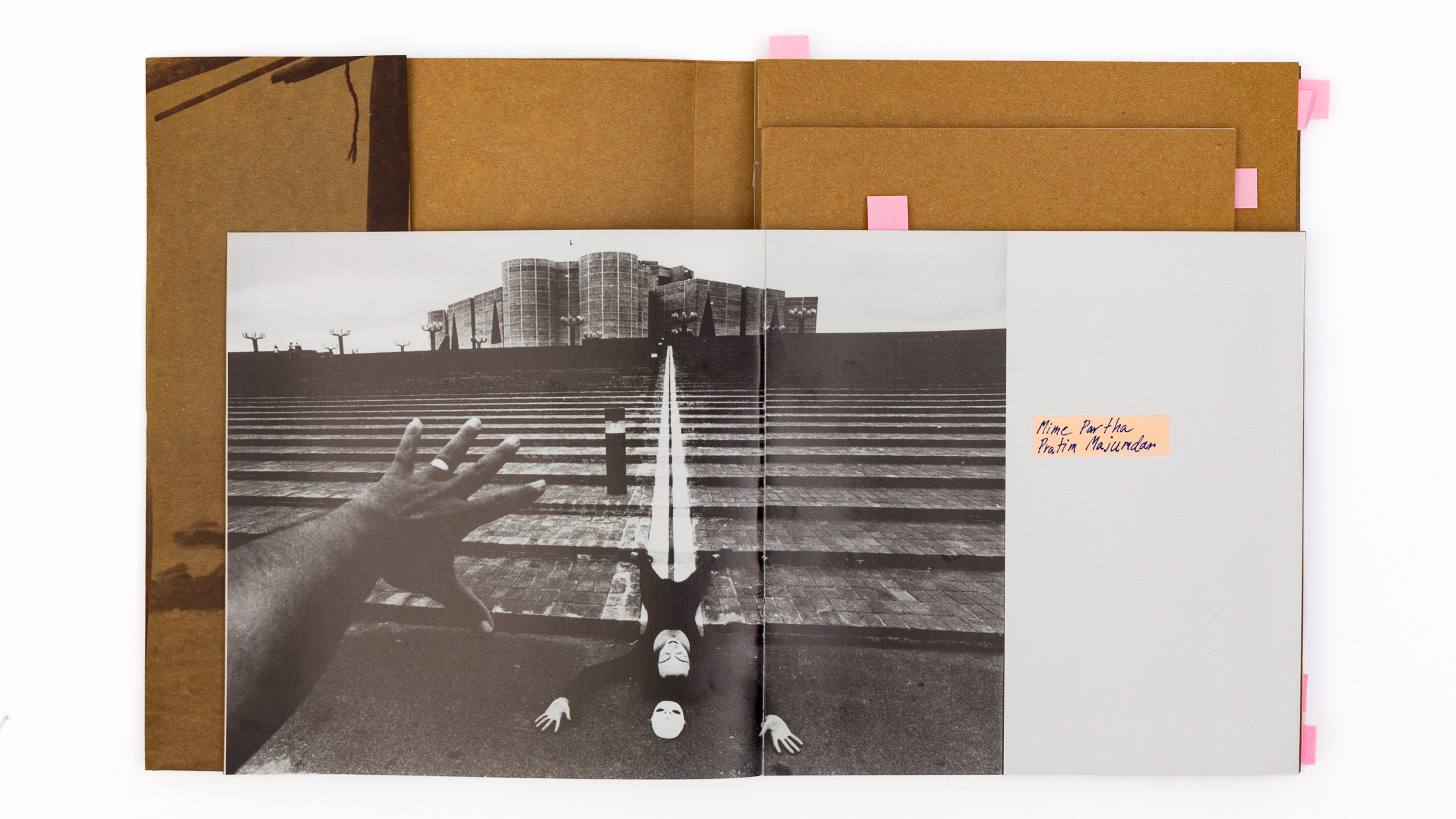

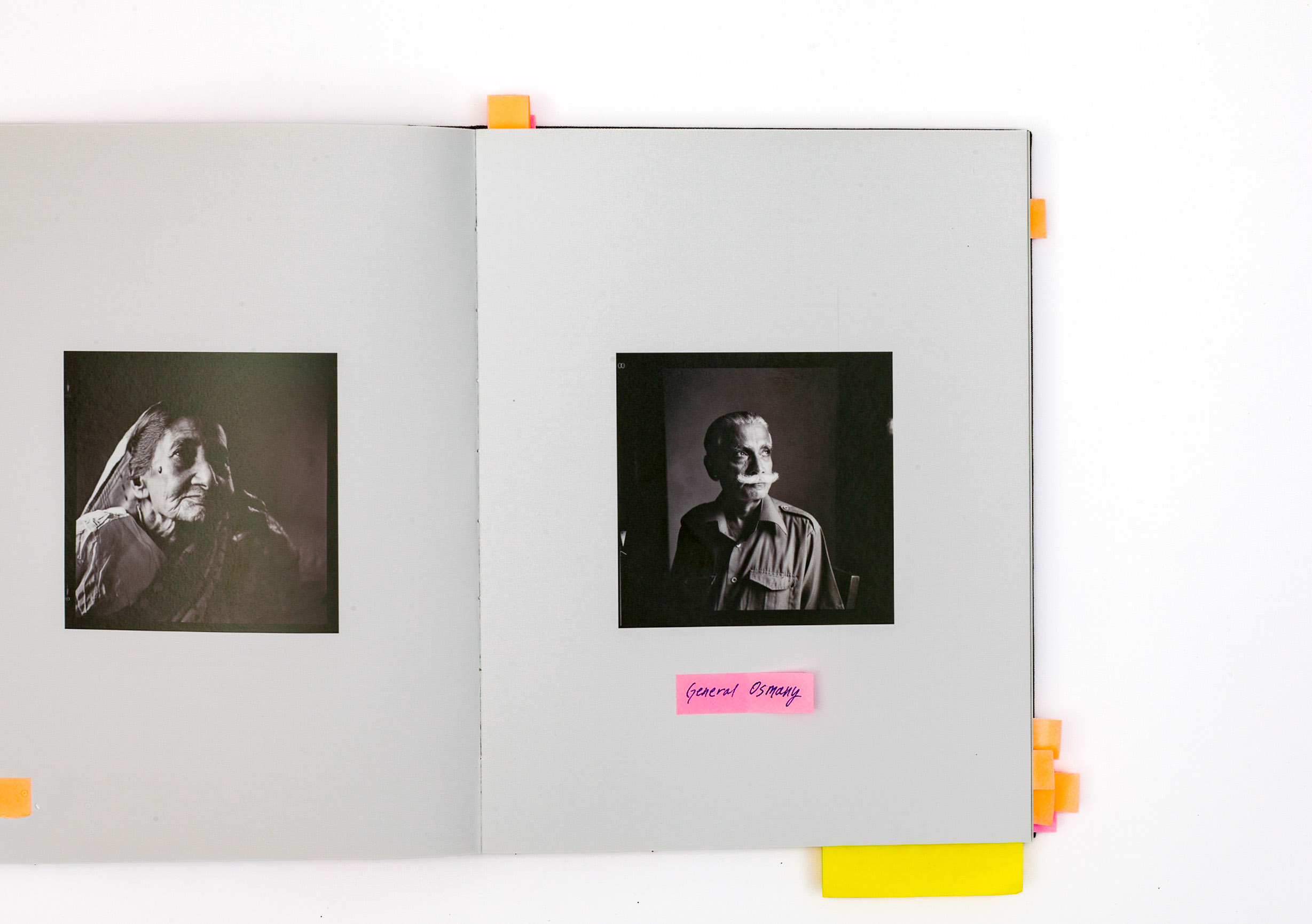

The 2019 edition of Chobi Mela (on the eve of pandemic) premiered a project by Naeem Mohaiemen, “What Was Chobi Mela And What Comes Next.” Borrowing from the title of Katherine Verdery’s book What Was Socialism And What Comes Next (1996), the project mapped out a 20 year history of three interlinked trends– photography in Bangladesh, the rise of arts organizations, and the evolution of technology. The project had two parts– in the first we rephotographed specific pages of the CM catalogues over the last two decades, highlighting early arrivals (e.g., Munira Morshed Munni, Dayanita Singh, Out of Focus). In the second part we built a twenty year timeline on the wall, with drawings by the art collective King Kortobbyo (Suborna Morsheada, Mehedi Hasan, Md Khairul Alam Shada, Pijush Talukder, Rakib Anwar). The project was coordinated by Sayed Asif Mahmud; research by Habiba Nowrose based on interviews with Shahidul Alam & ASM Rezaur Rahman; photography by Pranabesh Das & Debashish Chakrabarty. At a distance of six years, Naeem revisited the idea of a timeline, in conversation with photographer Habiba Nowrose and anthropologist Seuty Sabur.

Naeem: The written word is what I have worked with the longest. Starting in 1985, when I was editing Video Guide magazine in Dhaka; we were trying to find a way to describe, in stilted Bengali prose, the flow and melody of music videos– which most of us could not easily access. One pirated VHS tape would circulate through Filmfare (Sobhanbag) and Video Connection (Gulshan), and finally into the one VCR shared among twenty St. Joseph classmates. We were always describing the taste and feel of that rare visual encounter, through text. I have been pursuing the writing down of images, through words, for thirty years. That was the inspiration for the original timeline presented at CM in 2019– What Was Chobi Mela And What Comes Next.

Since the 2019 timeline a tide of accelerated events has washed over us. That list includes: Blackberry stopped making smartphones, Covid-19 lockdown, AI-generated imagery, Digital Security Act, Mannheim Photo biennale cancelled, internet shut down and reopened as a fifteen year regime collapsed, and so on.

Habiba, you did research for the original timeline. How do you see the idea of even creating a kind of timeline? Have you done more research on this since 2019?

Habiba: I worked on Bashirul Haque’s exhibition Wishing Tree for the next Chobi Mela (Shunnyo), which was his last project. I went through the designs of every building he created, interviews and the few writings about his work. We also brought in objects from his house, things he used regularly and pieces of furniture he had designed himself.

Naeem: We often say we don’t want to make history individual-centered. But at the same time, it inevitably becomes personal, because archives are tied to individuals. Manzoor Alam Beg was a significant figure, and he died quite early. When he passed away, there wasn’t a process in place for preserving things. Otherwise, we could say that after his death there might have been an exhibition like the one done for Bashir bhai—a research-based exhibition. But that culture, process, infrastructure—it didn’t exist.

Seuty: When it comes to envisioning that kind of memorialization, family and friends play a big role. That’s why I think class is very important in this too. The way families handle their history and archiving—that’s important too. How do you want to position your person—not only as an individual or a family member—but in a certain map, collectively? That collective effort didn’t exist back in Beg bhai’s time. That kind of social conditioning wasn’t there.

Naeem: As I wrote in my book Bengal Photography’s Reality Quest (2025), certain early photographers (e.g., Manzoor Alam Beg, Amanul Huq) paid a “pioneer’s penalty”– they innovated many things, but the infrastructure was not there to carry on the legacy. Habiba, Bashir bhai wasn’t in your immediate circle. Your work happened through Drik’s proximity. But if you made your own timeline, who would appear in it?

Habiba: I remember your timeline focused on technological landmarks, you pinned them along the way.

Naeem: What I focused on in 2019 was how technology kept moving forward, unstoppable. No matter which government came; even the nationalist parties once said they wouldn’t allow undersea internet cables because “Bangladesh’s secrets will leak onto the internet.” Now no one can say that—no one can stop these things anymore. In a way. I think both the evolution of Bangladesh’s photography scene and the country’s political developments are rooted in technology.

Habiba: I’d probably, because of my own interests, focus on movements. For example, the Road Safety Movement—that would definitely be one major event, in 2018. Those movements became broader—a kind of anger or protest against the system itself, and that feeling spread, especially because it was the students who took to the streets. So, I’d probably try to build a timeline around those major movements.

Naeem: What about earlier, 2014. Were you taking photos during Shahbagh?

Habiba: I did take some pictures. But at that time I was on a break from Pathshala. I’d finished my two-year program and taken a year off to do my master’s in Women and Gender Studies. In 2013 I finished at Dhaka University, and then went back to Pathshala again. There was a magazine called Ek Pokkho —some of those photos were published there. But honestly, most of us aren’t satisfied with our early work—I certainly wasn’t.

I actually faced a lot of criticism for taking too many photos of political events. While being part of organizations, I took so many pictures of the programs—like those related to the oil and gas movement, and various protests demanding rights. Probably my teachers got tired of seeing only that side of my work. So at one point I had to consciously practice holding myself back, to tell myself, “Okay, maybe the way I’m seeing things isn’t good enough.”

At the time, it felt like I was consciously choosing to focus on things outside what everyone broadly called “political.” Because there are other important things too, and those things are also political. I felt that needed to be said as well.

Seuty: I agree with Habiba that if you look at the period from Shahbagh in 2013 to July Uprising in 2024, the outburst of visual representation of political movements has set a tone. Pathshala helped set that tone, and there are many others, including Counterfoto members, finding their own styles and visual languages.

Naeem: Coming back to the timeline we made for Chobi Mela, the lack of gender diversity is startling. One project in a 20 year timeline, Onno Chokhe Dekha. I get surprised, again, how did this happen?

Seuty: There are many projects. Jannatul Mawa’s project about domestic workers and the middle-class household. Habiba’s work—shown at Alliance—that’s a very different kind of work. Jannatul Mawa —whether her photos were published or not— took pictures of all the movements. During my BRAC years, her daughter was also there taking pictures.

Taslima Akhtar has done a lot of work around garments, around oil gas movement, but her movement photos are fewer, partly because she was often directly part of the protests herself. Sometimes she photographed, sometimes she participated.

These works—Habiba’s, Mawa’s, and the others—I’d call them deeply feminist works. Feminist in every possible sense, in representation and approach.

Naeem: Onno Chokhe Dekha (Nurjahan Chakladar, Nargis Jahan Banu, and others), Farzana Khan Godhuli (AFP), Kakoli Pradhan, Juthika Howlader, Munira Morshed Munni, Farzana Hossain, Naima Perveen, Syeda Farhana, Momena Jalil, Salma Abedin Prithi, Snighdha Zaman, and others did important work in this strand. But one thing I notice—when we list these examples, they’re all vital and definitely should be included as important initiatives. But most are not from the 1970s. So if we make a long timeline, it becomes a problem—because I suspect a lot existed, but the records are gone.

Seuty: Exactly. Even our first female art photographer, Sayeeda Khanam.

Habiba: She was much earlier—

Naeem: Earlier and later. The 50s, 60s, and 70s. But that brings up the problem that our timeline has been too institution-focused. So now the question is how to unravel that and write new histories. And maybe a fully comprehensive timeline itself is a problematic idea.

Seuty: There are also new Indigenous photographers now, and they have a very different kind of visual language. Usually I try to follow up whenever I see something interesting from Pathshala or CounterFoto.

Habiba: I remember Aungmakhai Chak—and one of my students, Paddmini Chakma.

Naeem: Aungmakhai Chak (Kaali Collective), Denim Chakma, Jazong Nokrek, Rikki Nokrek Silkring, and others also photograph Adivasi communities. Drik Picture Library have formed a team, led by Saydia Gulrukh, doing a project on the history of Indigenous photographers from the Chittagong Hill Tracts. In their first research project “With my own eyes, in my own land” (Bandarban Archives 1909-2010), they featured Maung Ngwe Prue, Buddhajyoti Chakma, Chaw Thwe Phru Marma, Nu Shwe Prue, Chinmoy Murung, Ching Shwe Phru, Mong Shai Mrai, and Moung Boung Ching Marma. There was a three-day exhibition in Bandarban, and now they’re doing a long-term research project. On January 18th, 2026, during the next Chobi Mela, I’ll be in conversation with Saydia Gulrukh, Reng Young Mro, Ushing Mya Marma, and Roney Bawm.

Seuty: Paddmini Chakma’s work is worth mentioning. There was another photographer— the late Nurul Riad Han (Han Son Loft). Despite challenges, work is happening.

Habiba: Another point that strikes me, something not in the Chobi Mela timeline. In later years, for example, Saydia Gulrukh and others edited an online blog called Thotkata. Around that time, there was a very interesting phase. Despite all the criticisms of NGOs, they played a real role in mainstreaming feminist and gender politics. Of course there was backlash, criticism, and a very limited perspective—but those online digital platforms, Thotkata, Women Chapter, and a few others, created spaces where women could express their individual experiences. Very individualistic, yes, but those blogs became vehicles for awareness. They were hugely popular at that time.

Later, the Women Chapter faded a bit, and Thotkata started leaning more toward critical engagement and analytical tools—those who recognized it appreciated that. But eventually even those feminist blogs and writings began to recede slightly. Still, I think those platforms played a key role in spreading political and feminist awareness—bringing those conversations to a wider audience, especially younger generations.

Seuty: Yes, I think those platforms did play a role. And NGO activities too—some might call it “purple feminism” or even “decorative,” but they contributed.

Habiba: Those Public Nibigyan series of small books in Bangla—those were important too. They made research accessible, especially works centered on feminist politics. That accessibility mattered. So even though those were later publications—within the last decade or so—they’re significant.

Naeem: I was an early member of Thotkata, there were structural reasons that the organization faded. Samari Chakma had to go into exile in Australia for safety from Bengali persecution in Chittagong Hill Tracts. Several members– myself, Saydia Gulrukh, Nazneen Shifa, Nasrin Siraj Annie, and Hana Shams Ahmed went abroad for graduate studies. After they returned, everyone had full-time jobs–Shifa at IUB, Saydia at New Age and DRIK, myself at Columbia, Annie at BRAC. There was also activist fatigue of our generation, and the fact that after 2016 social media really took away reading publics from blogs. As Saydia puts it now, “blog has become shekele.”

Seuty: We have really shown our age by not mentioning Instagram in the discussion. Whether we like it or not, every photographer is using Instagram as one of their vehicles. So we have to give some credit to Instagram and TikTok—no matter how much we dislike them. Because those are the places where visuals are made, and where they disseminate. They even shape aesthetics. Whether we like it or not.

Habiba: My students are on Instagram.

Seuty: Yes, and honestly, we can’t even manage it properly—let’s admit it.